Key takeaways

- US stocks have outperformed non-US stocks in the last 10 years

- Over the last 25 years, US stocks have underperformed when the dollar has weakened

- The dollar could weaken if interest rates rise in Europe, or quicker inflation subsides faster there than in the US

- For many countries, short-term interest rates were stuck at 0%, but are now improving

- Despite potential upsides of international investing, diversification remains key for capturing any market positive returns regardless of location

The US stock market has far outpaced its global counterparts in recent years. In the ten years ending September 30, US stocks have returned 10.6% annualized, while non-US stocks have only returned 3.9%.

This has led many to question why they should even bother owning global stocks at all. Still, we are sticking with our global allocation. We see some near-term reasons to believe Global could easily outperform the US in the coming years, and some long-term reasons to value global diversification.

Dollar dominance

The first big near-term reason why non-US stocks could outperform is the dollar. While we do not believe the dollar’s dominant role in the world financial system will change anytime soon, that doesn’t mean the dollar can’t decline in value versus other currencies.

Remember that when you buy a foreign stock, whether directly or inside a fund, you are functionally exchanging dollars for the foreign currency and then buying the stock.

For example, let’s say you buy some Japanese stock on the Tokyo exchange. Say the first day you own it, the price of the stock doesn’t change, but the value of the Japanese yen declines by 1%.

Since you are a dollar-based investor, the value of your investment would also decline by 1%. In other words, your investment is worth 1% less in dollars even if it is unchanged in yen.

This is how returns on ETFs that invest in non-US stocks work, too. If you buy an international ETF, the return you get is a combination of how the actual stocks perform as well as how the value of the dollar changes.

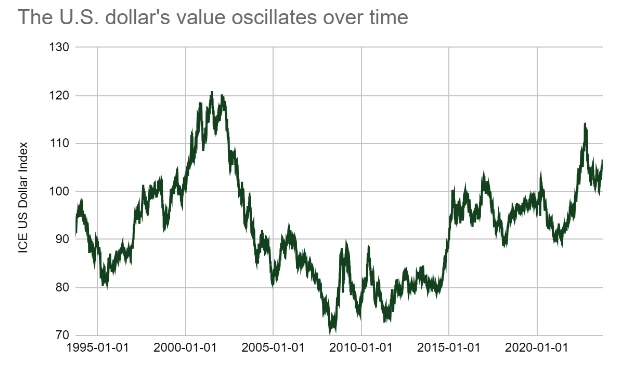

If we look back at history, we can see that the value of the dollar is a huge component in how international stocks perform. In the last 25 years, the Morningstar US has underperformed the Developed Markets, excluding the US index, 78% of the time when the dollar weakened. The reverse is also true. The US outperformed in 81% of years where the dollar strengthened.

It happens to be that the dollar has been mostly stronger against major currencies over the last decade. The ICE US dollar index, which measures the dollar against a basket of currencies, is up 32% over the last ten years ending September 30. However, looking over a longer trend of history, the dollar has had plenty of ups and downs.

Source: ICE

Source: ICE

Here, we see that while the dollar has appreciated over the most recent ten years. Historically, it has experienced major swings, mostly depreciating from 2001-2009 after appreciating substantially from 1995 to 2001. Note that from 2001-2009, non-US stocks were up 8.1%, while US stocks only rose by 0.5%.

Of course, we can’t know whether the dollar will keep getting stronger or suffer a reversal like it did in the early 2000s. However, there are some important reasons why the dollar could slip in value soon.

What causes the dollar value to change?

One of the biggest drivers of currency valuation is interest rates. International flows tend to go to wherever they can get the highest return. So, if interest rates rise in one country but not in others, that tends to attract big global investors to buy that currency and invest in that country to capture that relatively high interest rate.

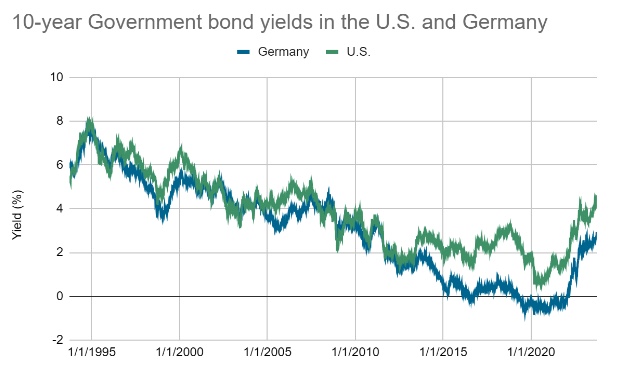

We can see these effects in action if we look at government bond yields and inflation rates in the US and the European Union over the last couple of decades. The chart below shows the government bond yields in the US and Germany, the latter being the largest government bond market in the EU.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

What we see is that both countries had about the same level of interest rates from the 1990s all the way up until 2013. At that point, US rates moved substantially higher than Germany (and have stayed higher ever since). Not coincidentally, 2013 is when the US dollar started to rise vs. the euro persistently, marking the period where US stocks drastically outperformed non-US.

There’s nothing saying that US interest rates should always be higher than other countries. If German rates were to rise closer to US levels, that could weaken the dollar. Again, we don’t know if this will happen, but as the interest rate chart above shows, the most recent period is unusual compared to the longer history.

Another significant factor in currency valuation is inflation. For most of the last 30 years, just about all rich countries were experiencing declining inflation rates, but that has reversed recently. In the 12 months ending September 30, US Core Inflation was 4.1%, similar to the EU at 4.5%. If inflation subsides quicker in the EU than in the US, that could also be a catalyst for the dollar to weaken.

The zero interest rate problem

It is important to remember that until recently, much of the world’s short-term interest rates were stuck at 0%. Economists believe that when interest rates fall to zero, it can cause special economic problems that can be difficult to overcome.

The technical term for this situation is called a “liquidity trap,” which has been studied by everyone from Paul Krugman to Ben Bernanke. This idea and its potential solutions dominated macroeconomic research in the post-Financial Crisis period.

The idea is this: the “right” interest rate for an economy is the one that balances savings with investment. In this case, “saving” means people putting money into safe assets, like a savings account at a bank. “Investing” means companies borrowing money to build new buildings, buy new equipment, and so on. Notice that these are two sides of the same action: the company that borrows from a bank to buy new machinery, and the bank gets that money from your deposit.

If interest rates are too high, tons of people will want to park their money in safe investments, but companies won’t want to borrow to create anything new. Banks will sit on too much cash, which in turn will slow the economy. If interest rates are too low, everyone will want to borrow, but banks won’t have any money to lend.

So what happens if the “right” interest rate is actually below zero? Practically, interest rates can’t get that low because no one would deposit money at a negative interest rate. It would be akin to having your deposit slowly confiscated. And banks wouldn’t lend at a negative rate either because it would be nonsensical to pay someone to borrow money from you!

As strange as it sounds, this exact occurrence has transpired in recent decades across many countries. It comes about when investors in a country demand a lot of safety and are, therefore, willing to accept meager interest rates. At the same time, companies don’t see a lot of good opportunities to expand and consequently don’t want to borrow.

If interest rates “should” be negative but are at zero, then you get the same effects as interest rates being too high: excess savings just sit idle at banks. This weighs on the economy. And if the economy is weak, stock prices will likely follow suit.

Once this occurs, it is hard to break out of it. It is challenging for the economy to rebound while interest rates are “too high,” but companies won’t want to invest in new projects until the economy strengthens. This is why economists use the term “trap” for this problem. Zero-rate environments can be difficult to shake.

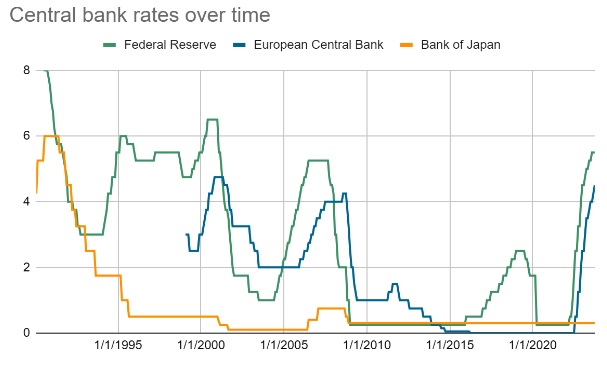

We all remember the period of a zero Federal Reserve target in the US, spanning from 2008 to 2015 and then again from 2020 to 2021. However, the liquidity trap problem was far worse in Europe and Japan.

The European Central Bank kept its target rate at approximately zero for seven years after the US began hiking in 2015. The Bank of Japan has kept interest rates at approximately zero since 1994, and they are only just now discussing the potential for hiking rates.

Source: Federal Reserve, ECB, Bank of Japan

Source: Federal Reserve, ECB, Bank of Japan

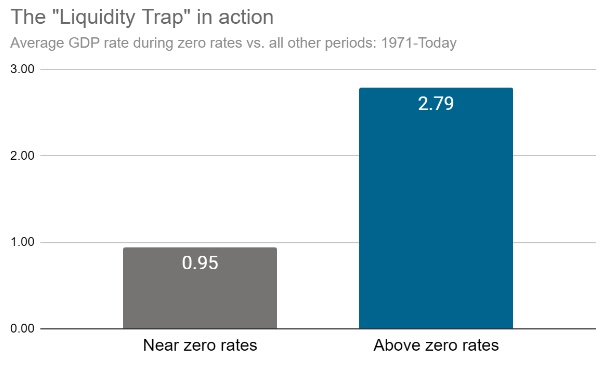

We can see how this liquidity trap phenomenon has impacted growth rates by comparing the periods where interest rates were zero versus when they were higher. To do this, we looked at the average GDP growth rate for all years where central banks in the US, EU, Japan, and the UK ended the year with an interest rate target at 0.5% or below. We compared that to all other periods.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Office for National Statistics, Cabinet Office, Eurostat

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Office for National Statistics, Cabinet Office, Eurostat

Here, we see that overall economic growth was very weak when interest rates were “trapped” at zero, and relatively strong in all other periods.

If economic growth is weak, it stands to reason that it would be difficult for stock prices to perform well. It could explain why those stock markets have underperformed since Europe and Japan were plagued with this zero interest rate problem for much longer than the US, particularly over the last ten years.

Looking forward, it could be that these economies are finally getting out of the trap. The ECB has hiked interest rates from zero to 4.5%. Even Japan now seems poised to start hiking rates soon. If both economies can continue to grow while interest rates rise, it tells us that the “right” interest rate is finally above zero.

Again, we don’t know for sure that this is the case. But like the points above about the dollar, this liquidity trap issue gives us a clear reason why international stocks might have underperformed in the last decade and why the problem may be fading away.

Diversification still matters

Lastly, we are believers in the long-term benefit of diversification. If you own a little of everything, you will likely hold some assets that perform better than others. It is easy then to look back and wonder why you owned the thing that underperformed. This is a version of what people who are questioning owning international stocks are doing now. Yes, with the benefit of hindsight, owning only US stocks would have done better from 2013 today.

But we don’t get to invest in the rearview mirror. We have to invest looking forward. If we are unsure which part of the world will be the best performer, we think owning at least a little of everything is the best move. That way, you know you will have at least some exposure to the best-performing asset.