Key takeaways

- Pull to par is a concept that applies to both individual bonds and ETFs - they both get pulled back up towards their maturity value every day, not just at maturity

- Liquidity costs for trading an individual bond can be up to 220 times more expensive than for an ETF, eating away at the return of the investor

- Concentration risk is also a factor when holding individual bonds; if one defaults, it could negatively impact the whole portfolio

- The opportunity cost of holding Treasury bonds can lead to much lower returns, compounded over time

At Facet, we use a mix of ETFs as our bond allocation in member portfolios. We firmly believe this is the best way to invest in bonds. However, there is a myth out there that owning individual bonds is more advantageous.

Not only can we show that the supposed benefits of individual bonds aren’t real, but we also argue that there are a number of hidden costs and risks that make owning bonds directly much less attractive.

Pull to par

The main benefit that gets attached to individual bond portfolios is that, supposedly, if you can hold a bond to maturity, you can’t lose money. The idea is that all bonds return principal at maturity.

Assuming the bond doesn’t default, you will get your initial investment back at that time, and whatever interest the bond has paid in the interim effectively guarantees you a positive return.

The bond’s price can rise or fall over the course of owning the bond, but that doesn’t change the fact that you will have a specified amount of principal paid to you at the end.

This idea is totally valid. The mistake often made is that the concept applies equally to a portfolio of directly held bonds as well as bond ETFs.

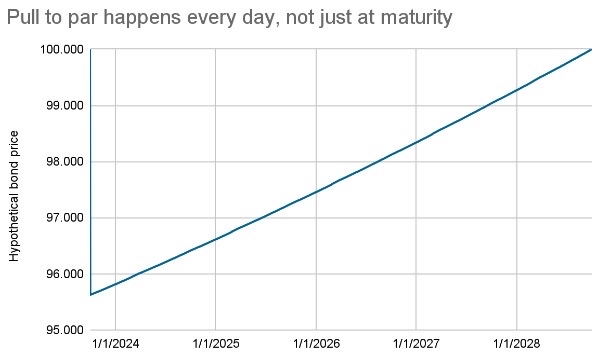

This stems from a concept bond traders call “pull to par.” In bond lingo, “par” is the bond’s principal value that gets returned at maturity. When interest rates rise, a bond’s price declines. For example, take a bond with five years to maturity that initially carried an interest rate of 4% and a price of $100. If interest rates were to instantly rise to 5%, that bond’s price would decline $95.6.

Now, it is true that if you waited the whole five years for the bond to mature, you’d still get your $100 initial investment back. The decline to $95.6 wouldn’t matter to you. However, that recovery doesn’t happen all at once at maturity. It actually happens in tiny increments every day. That’s why the term is “pull to par.” The bond’s price is slowly pulled back up toward its maturity value.

The chart below shows the hypothetical price of the bond we described above, assuming we start on October 1, 2023, and the bond matures on October 1, 2028. We have repriced the bond each day in between, assuming the yield remains constant at 5% after the first day.

Source: Facet calculations

Source: Facet calculations

In other words, each year, you would recover 1/5th of the price loss initially incurred. Each month, you would recover 1/60th, etc. On the last day before maturity, you’d only recover one day’s worth of that loss. That last day isn’t special.

So, if pull to par happens every day, not just at maturity, then it means that holding bonds within an ETF (or a mutual fund, for that matter) garners the same benefit as holding the bond directly. I.e., if you hold our hypothetical 5-year bond yourself or it is held within an ETF, it will be pulled to par in precisely the same way. There is no special advantage to holding bonds directly.

What happens if the ETF doesn’t hold to maturity?

Note that because of how pull to par works, it doesn’t matter whether the ETF holds a bond to maturity. This is because of the nature of bond yields. When you see the yield of a bond quoted, think of that as the total annualized return you can expect from now until the bond matures, encompassing both the interest the bond pays as well as any pull to par effects.

To illustrate this, let’s look at our hypothetical 5-year bond again. Initially, it had a yield of 4%, but because interest rates generally rose one day later, that yield increased to 5%. So, that new 5% yield means that if I hold the bond to maturity, I should have a return of 5% per year from day 2 of holding that bond to its maturity in 2028. That works out to just over 4% in interest return and just under 1% in price return from the pull to par effect. When added together, we get our 5% return.

What would happen if we sold this bond after one year and bought a different bond with the same 2028 maturity yielding 5%?

Remember that a bond’s yield is the return you’ll get if you hold to maturity. So, if you trade one bond with a 5% yield for another bond with a 5% yield, in effect, nothing has changed. From that moment on, you’ll be making 5% annualized.

Now, you might be thinking, if I sell my original bond before maturity, don’t I lock in a loss? This is true in a very narrow sense, but in terms of your actual dollar return, it doesn’t matter. The table below shows why.

Here, we assume two scenarios. In the first, you buy $10,000 of our example bond and just hold it to maturity. The table shows that you take a price loss in year one of $359 but also make $400 per year in income. The price gets pulled to par, so by the end, you have no price loss and have made $2,000 in income..

| Hold-to-Maturity | Sell after one year | |||

| Price Return | Income Return | Price Return | Income Return | |

| Year 1 | -$359 | $400 | -$359 | $400 |

| Year 2 | -$275 | $800 | -$359 | $883 |

| Year 3 | -$188 | $1,200 | -$359 | $1,370 |

| Year 4 | -$96 | $1,600 | -$359 | $1,862 |

| Year 5 | $0 | $2,000 | -$359 | $2,359 |

In the second scenario, we sell our original bond and buy a new bond with a 5% yield after the first year. We do “lock in” the $359 loss but make it up because the new bond generates more income. Or put another way, we don’t get any pull to par, but that doesn’t matter because the total dollars earned are the same: $2,000.

In the ETFs that Facet selects for our members, the vast majority of trading is just to handle inflows and outflows. However, as this illustration shows, it doesn’t matter if a particular bond is sold before maturity, whatever the reason. What matters is the portfolio’s overall yield.

Liquidity cost

In the example above, we did ignore one key factor in bond trading: transaction costs.

Anytime you trade any investment, there is a cost to do so. Some of those costs are overt, such as commissions for trading a stock. But some of those costs are hidden.

For example, in bonds, the broker you trade with makes their money by charging a slightly higher price to anyone buying a bond and giving a lower price to anyone who wants to sell. This difference is called a “bid-ask spread.”

In this case, the “bid” is the price a broker will buy from you, and the “ask” is the price they will sell a bond to you. The “spread” is the percentage difference between the two.

For example, if you go to a broker wanting to buy a particular corporate bond, they might say they are willing to sell at $97.5. But if you asked them to buy the same bond from you, they might only be willing to pay you $97. The bid-ask spread would be the difference between the two divided by the lower price, or $0.5 divided by $97, which is 0.5%

In bonds, the bid-ask can change a lot depending on the size you are trading. We can see this by looking at trade reporting on municipal bonds, which is required by law and collected by the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB).

For example, on October 13, 2023, a 4% bond for the State of California maturing in 2043 traded several times in sizes ranging from $15,000 to $30,000. In the scheme of the bond market, these are very small trades.

The average price brokers paid to customers selling the bond was $94.69. The average price customers paid to buy the exact same bond from a broker was $97.63. That equates to a bid-ask spread of 3.1%

A few days earlier, on September 26, this same bond was traded a few times in size of over $10 million. This is a close approximation for the kind of size in which large ETFs transact. On that day, the average price brokers paid sellers at that size was $96.01; to buyers, it was $95.88.

So, the bid-ask spread for large transactions was only 0.14%, but it was 3.1% for small transactions. In other words, regular investors buying individual bonds pay about 220 times the transaction cost! It might not seem fair, but this is the reality of bond trading.

Now, you might be thinking, if you buy a group of bonds today and just hold to maturity, you never have to pay this exorbitant bid-ask. There is some truth to that. However, that assumes you never add or withdraw any money from your portfolio.

Most Facet members are building up their portfolios by depositing new money regularly or spending some of their portfolios as they reach their objectives. Whenever this happens, you are incurring this bid-ask cost, which is eating away at your return.

Concentration risk

Not only is directly owning bonds expensive, but it is also dangerous. Typically, when individual investors own bond portfolios, they will invest in something called a “ladder.” This strategy involves buying 1-2 bonds that mature each year, going out something like ten years. You could possibly wind up owning something like 20 bonds or around 5% of your portfolio in each bond.

Unless those bonds are all Treasury bonds, there is some chance that one of your holdings will default.

For example, according to S&P, about 2.4% of all investment-grade corporate bonds have defaulted within ten years of issuing a new bond. That sounds low, but if you own 20 bonds, the odds that one of them suffers a default is about 48%.

Also, according to S&P, the average corporate bond loses 61% in a default scenario. So, if you are unlucky and one of your individual bonds defaults, you suffer a 61% loss on a 5% position in your portfolio. Remember that credit losses do not get a pull to par. Those losses are permanent. Just having one such event is a significant drag on your portfolio.

Facet’s ETF mix owns over 18,000 line items. Although the possibility of some defaults exists, each item is too insignificant to have a substantial impact. Remember that bonds are supposed to be a safety asset. Maximizing diversification is, therefore, all the more important.

Opportunity cost

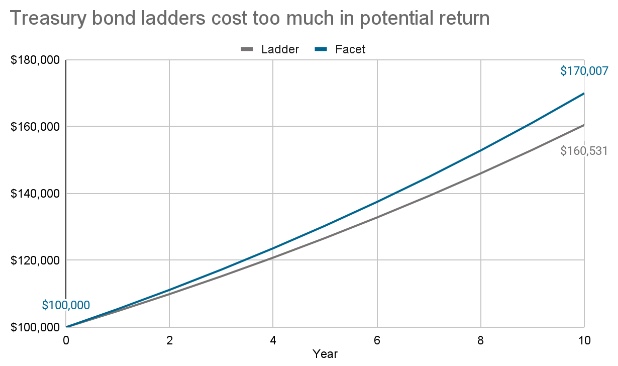

One way you can avoid default risk is to only own Treasury bonds in your portfolio. The problem with this is that you give up a lot of yield by only owning Treasury bonds, which in turn means your future returns will be lower.

For example, as of October 16, a Treasury bond ladder from 1-10 years yields 4.85%. Facet’s bond mix for tax-deferred has a yield of 5.45%. That might not seem like much, but the difference will compound over the subsequent years.

The chart below shows the cumulative growth of $100,000 invested at 4.85% (Ladder) and 5.45% (Facet). You can see that the difference amounts to almost $10,000 over a ten-year period.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

It gets worse if you use a Treasury ladder in a tax-paying account. Facet’s bond allocation for members in higher tax brackets yields 4.03% tax-free. For someone in the maximum Federal tax bracket, the Treasury ladder yields only 3.05%. Earning those yields over ten years would amount to $13,000 more in your pocket for investing in the ETF vs. the ladder.

Final word

On a personal note, before I came to Facet, one of the jobs I had was managing bond portfolios. I ran both mutual fund portfolios as well as individual bond portfolios. I have personally seen the high cost of trading up close, and I want no part of it. For that reason alone, I used to tell my clients that I would never own bonds directly, even if I had $100 million to invest. If you add to that the diversification and future return benefits, I believe owning ETFs is a no-brainer over owning bonds directly.