The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Tax-loss harvesting is a good way to reduce what you owe in taxes on gains from your investments.

- With individual stocks, it’s harder to use losses for tax benefits because of the "wash sale" rule, which says you can't claim a loss if you buy the same or a very similar stock within 30 days of selling it.

- ETFs make tax-loss harvesting easier because you can almost always find a very similar ETF to the one you own that's not "substantially identical.

- Most importantly, you should never sacrifice portfolio quality for tax benefits.

If you're going to make money investing, you're also going to wind up paying some tax. But there are some ways you can reduce your tax burden. One of those is tax-loss harvesting. Here’s what tax-loss harvesting is, and some of our thoughts on how to best execute it.

How the IRS treats investment sales

When you sell some investment for a profit, the IRS considers that income (or more specifically a “capital gain”) and you're going to owe taxes on that profit. However, the opposite is true too. If you sell an investment at a loss, the IRS allows you to consider that a deduction.

You can use that loss to offset capital gains from other sales. If your total losses are greater than your gains in any given year, you can carry over the losses into future years. You're even allowed to use up to $3,000 per year of these losses to offset your ordinary income.

Of course, in a perfect world, you would never have any losses in your investment account. In the real world, however, every investor loses money from time-to-time. You may as well get some benefit from those losses. This is where tax-loss harvesting comes in.

Realizing the loss doesn’t mean making the loss permanent

Tax-loss harvesting involves selling one investment and buying another investment, presumably one that is closely related to your original position. If you do this right, you can realize tax losses during market volatility, and still get all the benefits when stocks rebound.

With individual stocks, this is tricky because of something called the “wash sale rule.” The IRS doesn’t allow you to realize a loss for tax purposes if you buy a “substantially identical” security within 30 days of your sale.

For example, say you buy J.P. Morgan stock and it suffers a 10% decline. If you sell it, you book that 10% loss as a future tax deduction. However, because of this wash sale rule, you can’t buy it back the next day and still claim that loss on your taxes. You’d have to wait 31 days before buying it again.

This creates a problem because what if J.P. Morgan’s stock jumps higher during that 31 waiting day period? It's pretty common for stocks to get most of their gains from just a few big up days over the course of a year. What if some of those big up days occur while you're out of the stock?

Dealing with the wash sale rule

There are some solutions. First, you can sell the J.P. Morgan and buy a similar stock, for example Bank of America. You hold for 31 days and then you can buy J.P. Morgan stock back. You can claim the loss while keeping your money invested.

This isn’t a perfect solution, however. If Bank of America stock jumps higher during the 30 days and you sell it, now you have realized a tax gain. Worse, this is what is called a “short-term capital gain” because you held the stock for less than a year. Short-term gains are typically taxed at a higher rate than long-term gains. This could potentially wipe out the benefit of the tax-loss harvest in the first place.

Tax-loss harvesting with ETFs

With ETFs, tax-loss harvesting is much easier, but there are still some pitfalls.

The main thing that makes ETFs easier to tax-loss harvest is that you can almost always find a very similar ETF to the one you own. If you're trying to sell a large-cap growth ETF for the tax loss, you can just buy some other large-cap growth ETF. You aren’t really changing your portfolio exposure, just realizing the tax loss.

However there are still some complications. Remember that the IRS wash sale rule says you can’t buy a security that is “substantially identical” to the one you sold within 30 days and still write off the loss. Perhaps surprisingly, there is no official definition of “substantially identical.” For example, is the SPDR S&P 500 index fund substantially identical to the iShares S&P 500 index fund?

The IRS has never ruled on this, so officially, we don’t know.

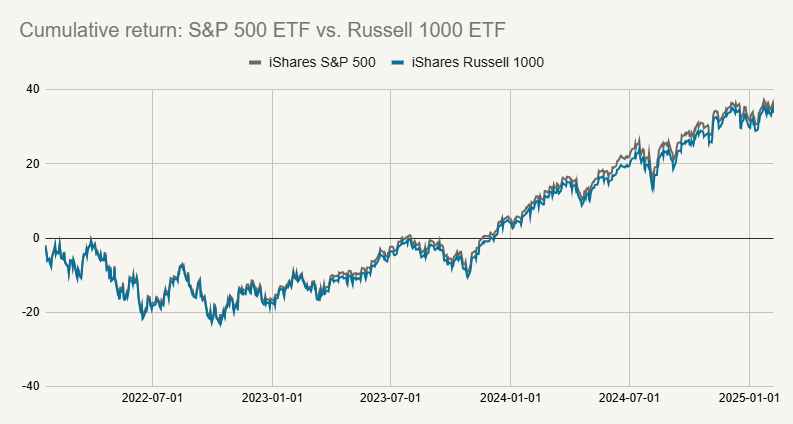

Among professional advisors, it's generally agreed that best practice is to use an ETF that follows a different index. So here at Facet, if we sold an S&P 500 fund for a tax loss, we’d buy something like a Russell 1000 fund with the proceeds. The chart below shows the performance of the iShares S&P 500 fund vs. the iShares Russell 1000 fund.

Source: iShares

Both large cap US funds, but not based on the same index, and therefore less likely to be deemed “substantially identical.”

Be ready to hold for the long-term

This gets us to the second pitfall of tax-loss harvesting with ETFs. When the market drops significantly, it's quite common for it to also rebound quickly. In other words, at the end of the 31 day waiting period, the ETF you bought could be at a decent gain. So maybe we sold a S&P 500 fund for a loss, bought a Russell 1000 fund, but now that Russell fund is at a gain.

This is the same problem we mentioned with individual stocks: you can’t sell the Russell fund without realizing a tax gain, basically eliminating all the benefit of the tax-loss harvest.

When you do a tax-loss harvest, assume you're going to hold the substitute fund for the long-run. If your only substitute option is an inferior fund, don’t bother with the tax-loss harvest at all.

Never sacrifice portfolio quality for tax benefits

There are advisors, especially among the roboadvisors, that tax-loss harvest too aggressively. When the market is in decline, it tends to decline quickly. If you set your trigger for tax-loss harvesting too small, you’ll wind up doing several in quick succession.

The problem becomes that, because of the wash sale rule, if you wind up doing many tax sales in short order, you could wind up owning your 4th, 5th or 6th best ETF idea for a given allocation.

We don’t think it likely that the 6th best option is still a good option. And remember, because the market tends to rebound suddenly, you could wind up holding that 6th best option for a long time.

Tax-loss harvesting is great, and you should definitely do it. But not if it comes at the expense of portfolio quality. Don’t let the tax tail wag the portfolio dog. Build a great portfolio first, worry about taxes second.

At Facet what we’ve done is used historic data to build a simulation dataset. We’ve then identified within the simulation what trigger points maximized benefit from tax-loss harvests without sacrificing portfolio quality in any way.

Of course, these are just simulations, and there’s no guarantee they will be perfectly accurate. However, we prefer this science-based approach to the more aggressive approach taken by some others in the industry.

Tax-loss harvesting is part of what we call “tending the garden.” It's one of the little things that you should be doing to maximize the overall benefit from your investments. But you have to do it right, otherwise you could either degrade your portfolio’s allocation or just waste your time and not actually get any tax benefits.

Tom Graff, Chief Investment Officer

Facet Wealth, Inc. (“Facet”) is an SEC registered investment adviser headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland. This is not an offer to sell securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This is not investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.