The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Dividend-paying stocks have underperformed other types of stocks

- Dividend stocks do not necessarily protect a portfolio on the downside

- The average high-dividend stock is less profitable, growing slower, and has more debt than the average company

- Targeting high-dividend stocks may result in a portfolio of highly leveraged, slow-growing companies

- Investors should not view dividend rate as a unique characteristic and should aim for both income and appreciation

“The true investor will do better if he forgets about the stock market and pays attention to his dividend returns and to the operation results of his companies.” - Benjamin Graham

Graham’s sentiment in this quote is shared by many investors even today. Returns from dividends can feel more real and sustainable than stock price appreciation. After all, a dividend is cash in your pocket.

Moreover, it seems intuitive that dividend-paying companies must be more established and stable to afford to pay out consistently.

Unfortunately, the reality is more complicated than this. It turns out that dividend-paying stocks are not more stable, predictable, or better performing than other kinds of stocks.

In fact, focusing on income over price appreciation can be dangerous for your portfolio.

Here’s why.

Dividend stocks have underperformed other kinds of stocks

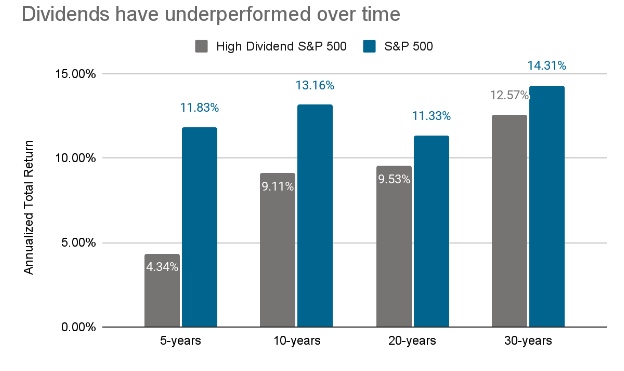

The first simple reality is that high-dividend stocks have performed worse than the broad market over time.

The chart below compares the S&P High Dividend index, which consists of the 80 highest dividend-yielding stocks within the S&P 500, and compares that to the whole S&P 500.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices. Data as of 5/26/2023

Dividend stocks don’t protect your portfolio on the downside

You may have heard a claim that dividend stocks are safer or more stable than other kinds of stocks.

For example, in calendar 2022, the S&P High Dividend index was only down 1.1% vs. -18.1% for the whole S&P 500. However, this kind of downside protection has not been consistent over time.

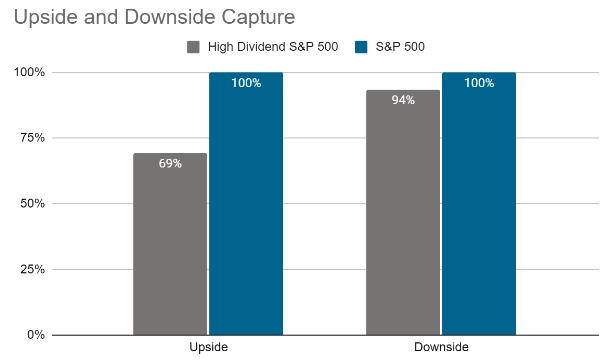

To test this, we ran an analysis called “upside and downside capture.” This test measures what percentage of the upside or downside return an asset realizes in any given period.

Here’s the result.

Source: S&P Dow Jones Indices and Facet calculations

These percentages mean that we expect dividend stocks to suffer 94% of the downside when the S&P falls but capture only 69% of the upside.

Put another way, if the S&P rises by 10%, this analysis suggests dividend stocks would tend to only rise by 6.9%. Whereas if the S&P falls by 10%, the dividend stocks would barely offer any protection, falling by 9.4%.

When running this capture analysis, we generally want to see the upside percentage higher than the downside percentage. This is especially true given that stocks typically rise more often than they fall.

Remember that the S&P 500 has increased in 16 of the last 20 years. You can’t afford to give up this much upside only to get a slight amount of downside protection.

Why have dividend stocks performed so poorly?

The average high-dividend stock is fundamentally different from its lower-dividend peers. These differences probably explain why they have underperformed historically and could portend underperformance looking forward.

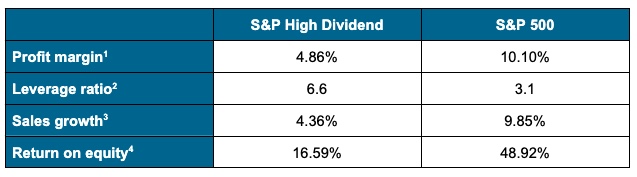

First, let’s look at this statistically. The following table shows the average of key financial metrics for the S&P 500 and the high-dividend index.

Source: Bloomberg, company reports

This table shows that the average high-dividend stock is less profitable, growing slower, and has more debt than the average company overall.

This isn’t a coincidence. Companies that pay high dividends tend to have no other good use for that capital. In contrast, companies still in growth mode tend to want to reinvest in their business.

Moreover, companies that aren’t growing commonly use debt to generate shareholder returns. This includes making acquisitions or borrowing money to fund dividend payments hence why our universe of high dividend-paying companies has a higher leverage ratio than other companies.

Should we own high-dividend companies at all?

We’re not saying investors should avoid these companies at all costs. Rather, it’s best not to view the company’s dividend rate as a unique characteristic.

Targeting a set of high-dividend stocks will result in a portfolio of highly leveraged, slow-growing companies. As a result, we do not believe this approach will lead to investment success.

We started this piece with a quote from Benjamin Graham which seemed to praise dividends. But perhaps this Graham quote sums it up better:

“The stockholder wants both income and appreciation, but in general the more he gets of one the less he realizes of the other.”

Tom Graff, Chief Investment Officer

Facet Wealth, Inc. (“Facet”) is an SEC registered investment adviser headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland. This is not an offer to sell securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This is not investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.