The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Tariffs are a tax on imported goods, which typically cause the price of these goods to rise for consumers.

- Economists generally agree that tariffs cause lower growth and higher prices.

- However some argue that tariffs are necessary to either negotiate more fair trade terms or to protect domestic industries from stronger foreign competition.

- While there is reason to think that the impact of tariffs might be smaller in the U.S. compared to other countries, it still introduces risks to the economy.

On the campaign trail, President-elect Donald Trump promised to enact across the board tariffs. He proposed a universal 20% tariff on most imported goods, and a more aggressive 60-100% charge for products coming from China. Could tariffs reignite inflation? Could this pose new risks to the economy? Here are our takes on how Trump’s tariff plan could play out.

What are tariffs?

A tariff is just a tax on imported goods. It is sort of like a toll that gets paid when goods enter the country, like when you pay a toll to cross a bridge or go through a tunnel. The tariff can be applied differently to different kinds of goods and based on country of origin. For example, Trump has specifically targeted goods coming from China for more severe taxes.

Technically, whatever company is importing the good is paying the tariff. But because this raises the cost to the seller, some of the cost of this tax tends to get passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. This is why it's generally believed that tariffs cause inflation.

Why economists don’t like tariffs

Virtually all economists would say that tariffs are bad for the economy in a vacuum. In an ideal state, countries would specialize in the kinds of goods they are comparatively best at producing. They would then sell those goods to the rest of the world, and use the income to import whatever goods they don’t produce as efficiently.

The idea is that if every country specialized in the things they are best at producing, then we’ll have more total production around the globe, and at a lower cost, vs. if every country tried to make everything themselves. Everyone would be better off.

This is actually quite similar to what you personally do. You spend most of your time at your job, which is what you’ve decided to specialize in. If you are a nurse, your household is exporting nursing services.

When you come home, you don’t try to make your own toaster or area rug or produce your own TV show. You let other people specialize in producing those things. You use your income from your specialty to import these items into your household.

The idea here is that countries aren’t so different from you and me. At least, this is true in an ideal world.

Tariffs can be a negotiating tool

Of course, we don’t live in an ideal world. In the imperfect world in which we actually live, there are some arguments for when tariffs might make sense.

One is that tariffs can be used as a negotiating tactic. If some countries are engaging in unfair trade practices, the threat of tariffs could be used to counteract such practices, and perhaps spark a renegotiation of the terms of trade.

For instance, China uses government money to subsidize the production of certain goods. A subsidy like this can make it so that Chinese companies can produce certain things at a lower cost than other countries, not because they are better at producing it, but because they are being given an advantage by their government.

Tariffs can be a way of combating this. If a Chinese factory can make some item cheaper just because the government gives it a $2 subsidy, then the U.S. could offset this advantage by charging a $2 tariff.

Ideally this turns into a negotiation tactic. You attempt to get all countries to lower their subsidies and tariffs all at once and therefore get closer to the ideal world I talked about in the beginning.

Protectionism

The other argument for tariffs is what’s called protectionism. This is where a government determines that it wants to protect some domestic company or industry from foreign competition. Generally this is because the foreign producers are outcompeting the domestic ones, perhaps because of product quality, cost or both.

Usually this is justified because the government determines that having a certain domestic industry is important, even if it means propping up weaker competitors. For example, this is why there are so many national airlines around the world. Air travel might be cheaper if there were a handful of larger competitors, but countries don’t want to be without a domestic airline. So there’s a lot of government support for that industry.

Both President Trump and President Biden have used this justification. Trump has talked about a “manufacturing renaissance” spurred on by his tariff plan. The Biden administration came to this conclusion about semiconductors. The CHIPS Act created all kinds of subsidies aimed at bringing more semiconductor manufacturing into the U.S.

Protectionism almost by definition results in higher cost goods to consumers, since lower cost foreign goods are being driven out (or made more expensive with tariffs). Those that advocate for protectionism counter that while costs may be higher in the short-term, by insulating companies from foreign competition, you will given them a chance to grow. Over time they will become more efficient. Not only will that lower consumer costs, but it will also mean the nation enjoys a thriving new industry.

This makes a lot of sense in theory, and lot of countries have tried this, but very few have succeeded. Companies that aren’t subject to competition tend not to focus enough effort on innovating. If they aren’t innovating, they are just falling further and further behind the global competitors. Ironically this may mean they require more and more protection.

Impact of Trump’s specific plan

On the campaign trail, Trump has talked about a universal tariff of up to 20%, with special tariffs on China of 60-100%. So what would the impact of something like that be?

The standard economic theory would say any broad based tariffs like this will cause higher prices and less economic growth. However there are reasons to think that the impact on the U.S. would be somewhat smaller than it would be in other countries.

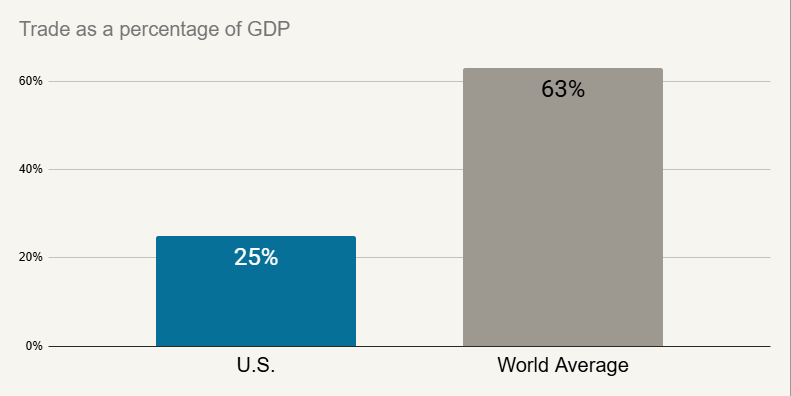

In the U.S., total trade, that is the value of imports plus the value of exports, is only about 25% of GDP. That’s one of the lowest levels anywhere in the world, and easily the lowest among wealthy countries. The global average is 63% of GDP.

Source: World Bank

This is just because the U.S. is so large. A lot of trade in the U.S. is between Texas and Oklahoma instead of being across national borders. That’s going to make the impact of tariffs smaller here than it would be in other countries.

Consumer prices

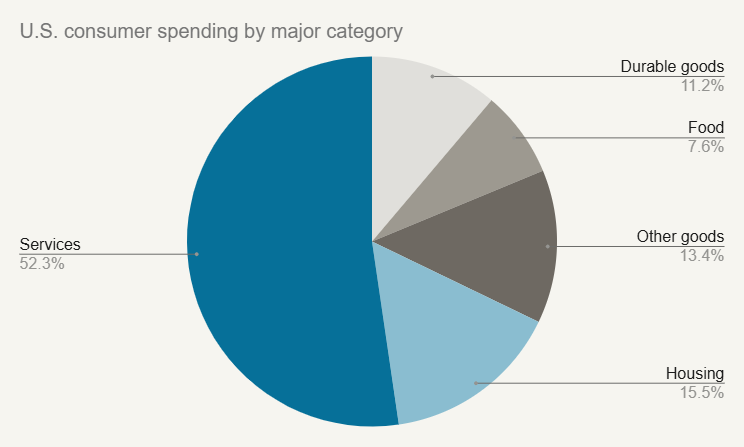

While tariffs are very likely to cause prices to rise, this effect would be mitigated by consumer spending habits.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

The chart above shows that about ⅔ of consumer spending is either on services or housing, neither of which is typically traded internationally. Most trade occurs in “durable goods” which just means anything that isn’t consumed. This includes things like automobiles, household appliances, consumer electronics, etc. This only makes up 11% of spending.

So even if there were to be a pretty large increase in the price of these goods, the impact on overall consumer prices would be mitigated.

Lastly, economics tend to think of tariffs as having a one-time impact on prices, not an on-going effect. E.g., if a 20% tariff might cause the price of all foreign goods to rise by 20%. But there’s no reason to expect prices to keep rising from there. In that sense, it is a temporary impact on inflation.

Risks for financial markets

The most immediate risk for markets is a response from the Fed. Even a relatively small increase in inflation, say 0.2%, 0.3%, something like that, could force the Fed to act. As we talked in our Fed reaction piece, inflation has been sort of stuck around 2.6-2.7% the last few months, and this already has the Fed reconsidering how many rate cuts they are going to do.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

If inflation actually starts rising, even a little, the Fed could even consider hiking rates. Even though we are arguing that the impact of tariffs could be relatively small, it could easily be large enough to change the Fed’s current policy position.

At the very least, any kind of upward inflation pressure is going to keep interest rates higher than they would have been otherwise. Higher rates do have economic risks: it hurts the housing market, hurts commercial real estate, and increases recession risk a bit on the margins.

What are we doing about it?

There are three portfolio positions we have taken that could be impacted by tariffs. In each case, the impact of tariffs is just one of several reasons why we favored the position, but are especially apt in a world of rising tariffs.

- Underweight emerging markets stocks. In general, emerging countries rely more on exports for economic growth, and Trump is specifically targeting China which is the largest emerging markets country.

- Underweight companies with high debt burdens. These are the companies that are more vulnerable should interest rates remain high. One area to be especially cautious is real estate.

- Underweight interest rate risk. In bond portfolios, we are positioned to be more defensive should interest rates rise, especially in longer-term bonds. This means that if longer-term interest rates were to rise, our allocation should protect capital a bit better.

We think the combination of these positions could give portfolios some defense should the impact of tariffs be relatively large, while not being overly exposed if tariffs are quickly reversed or simply don’t have as large of an impact.