The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Fed Cuts Rates Despite Government Shutdown: The Federal Reserve cut interest rates by 0.25% in October 2025, relying on private data like the ADP report to make its decision while "flying blind" during the government shutdown.

- Weakening Job Market Spurs Fed Action: Growing evidence of a slowing labor market, including weak private payrolls and concerns of the economy reaching "stall speed," was the primary motivator for the Fed's rate cut.

- Fed Bets Tariff-Driven Inflation is Temporary: Despite Core CPI remaining elevated near 3%, the Fed believes the recent inflation spike is a temporary, one-time price adjustment from tariffs and not a persistent trend.

- More Rate Cuts Likely as Risks Remain: Fed Chair Powell signaled a clear concern for employment over inflation, suggesting more rate cuts are likely in December 2025 and into 2026 if the labor market does not rebound.

The Federal Reserve cut its target for interest rates by 0.25% at the October meeting. For a long time, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has told us the Fed’s decisions would be “data dependent.” However, with the government having been shut down for almost all of October, there is very little new data for the Fed to analyze since its last meeting in September. So what led Powell and company to this decision? What does it say about the outlook for rates in the coming months? And how might this impact financial markets? Here are our thoughts on what happened at this Fed meeting and what we think might be coming next.

The Fed is flying (almost) blind

Powell began his post-meeting press conference by reminding viewers that the Fed is governed by a dual mandate: “maximum employment and stable prices.” Unfortunately, with the government shutdown, the Fed isn’t getting any updates on any of the traditional measures used to gauge both of these goals. Hence, the inspiration for the title of this piece: the Fed is mostly flying blind right now.

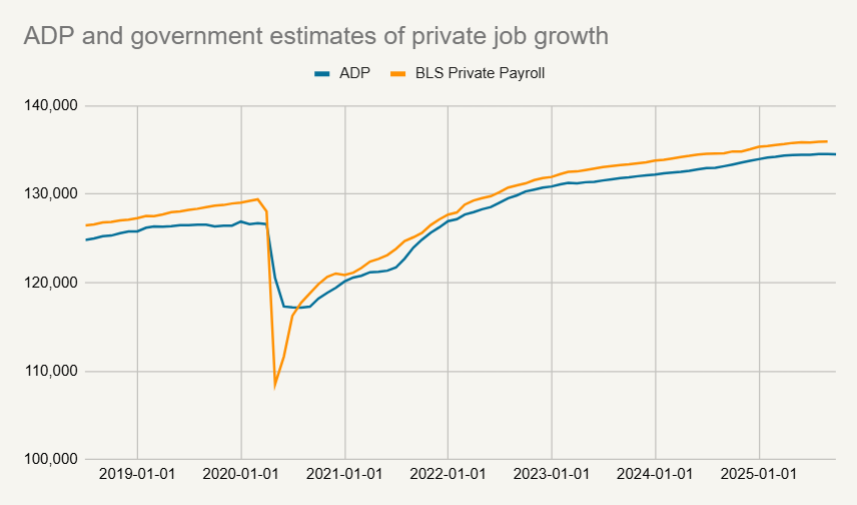

We say mostly because there are a wide variety of data sources available that don’t rely on government statistics. For employment, ADP, which is a large private payroll provider, has been publishing an estimate of private job growth for many years. While there can be significant differences between ADP’s estimate and the official Bureau of Labor Statistics estimate of job growth in a given month, over time the two track each other very closely.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, ADP

ADP estimated that the U.S. economy lost 35,000 private jobs in September. Note there can be significant variation in jobs numbers from month to month, so we don’t want to overreact to any one number. However, any month where total jobs actually contracts is certainly concerning.

Other non-governmental employment figures suggest weak job growth. The Institute of Supply Management has long published two business sentiment surveys, one for manufacturing and the other for services. Each includes a question on hiring intentions. The September version of both of these surveys indicated companies intended on shrinking headcounts.

We are also getting private estimates of new unemployment claims. Typically this figure is also published by the Federal government, however the actual claims are administered by state governments. The raw data has been made available, and economists from both Bloomberg, Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan have all tried to replicate the methods used to report these figures nationwide. Based on these unofficial estimations, jobless claims have been mostly steady, but with a surge of claims from recently laid off Federal workers.

So while we don’t have the official jobs figures we typically get from the Labor Department, we do have some idea about how the employment market is doing. It certainly looks like the labor market weakness we have seen the last few months has continued, at least through September. The October jobs report from ADP will be coming out on November 5.

Powell lamented the lack of government data, but did emphasize that the Fed still has good sources of information. Beyond the private data providers I mentioned here, the Fed also keeps a network of business contacts they call on to get intel on the state of the economy. Powell expressed confidence that even if the government shutdown were to continue longer, the Fed’s informal tools and contacts would be enough. “I think if there were significant or material change in the economy, one way or the other, I think we’d pick that up through this.”

Fed more worried about employment than inflation

The one area where the Fed isn’t flying blind is inflation. The Labor Department employees who compile the Consumer Price Index (CPI) report were actually called back to work, without pay, to publish this key inflation data. This wasn’t for the Fed’s benefit (or for Wall Street’s) but rather because the CPI is used to calculate cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security. Regardless, it did give us some clues about the state of one side of the Fed’s mandate.

The bad news is that inflation is clearly still too high. Excluding food and energy, consumer prices rose 3.0% over the last year. While the Fed uses a different inflation measure for its official 2% inflation target, we can say with confidence that CPI at 3% is out of the Fed’s comfort zone. In his press conference, Powell described inflation as “somewhat elevated.”

Despite this the Fed seems comfortable cutting rates. This is partly because the Fed is especially concerned about the weakness in job growth. But it is also probably because the Fed is becoming increasingly confident that the only thing driving inflation higher is tariffs. As Powell has said several times, there is a good chance that the “effects on inflation will be relatively short lived” if tariffs are the primary driver. This is because while companies will probably raise prices in response to tariffs, there is no particular reason why they should keep raising prices.

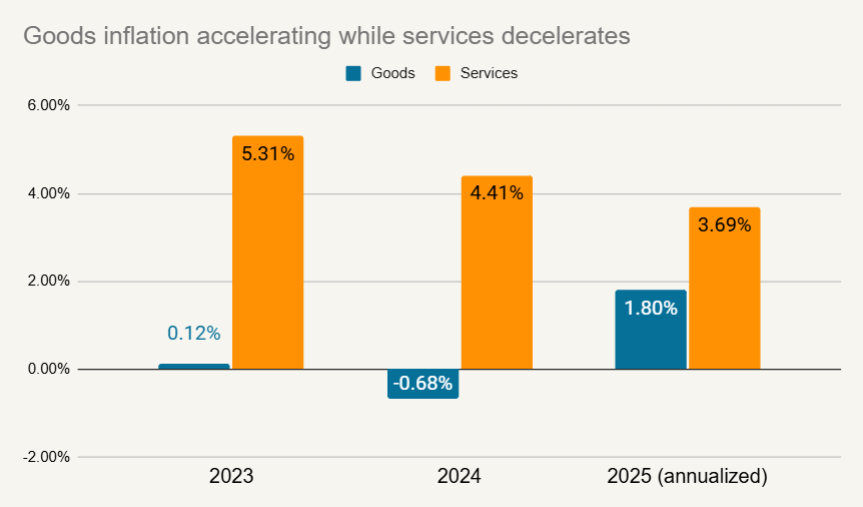

The data supports the idea that recent inflation has been mostly driven by tariffs. The chart below shows the inflation rate for goods vs. services, both excluding food and energy.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Tariffs are logically going to mostly hit physical goods, whereas most services don’t trade across borders. So the fact that goods inflation is accelerating while services is decelerating does suggest tariffs are causing most of the recent uptick in inflation.

If Powell is right, and tariff-based price increases mostly all hit in one short burst, then the rate of inflation should start subsiding in the coming months. We may be already seeing this, as September’s inflation rate came in solidly below that of either July or August.

Impact of government shutdown

Powell was asked a few questions about the current government shutdown. Per usual, Powell was careful not to wade into politics. He did say that the shutdown “will weigh on economic activity.” The primary effect stems from the temporary halt in spending by furloughed federal employees and a pause in payments to government contractors, which subtracts directly from quarterly GDP. However, this lost output represents a very small fraction of the multi-trillion dollar U.S. economy. Furthermore, because furloughed workers have historically received back-pay after past shutdowns have ended, the impact on consumer spending is often a delay rather than a permanent loss, which helps to mute the long-term economic damage. Hence why Powell predicted that any impact from the shutdown “should reverse after the shutdown ends.

Could AI save the economy?

As we have written a few times in the past, the U.S. has never experienced job growth this slow without the economy subsequently falling into a recession. Fed Governor (and potential candidate to become Chair) Chris Waller has called this a “stall speed.” In other words, the idea that the economy is kind of like an airplane: if it isn’t growing fast enough to spur healthy job growth, it risks falling out of the sky.

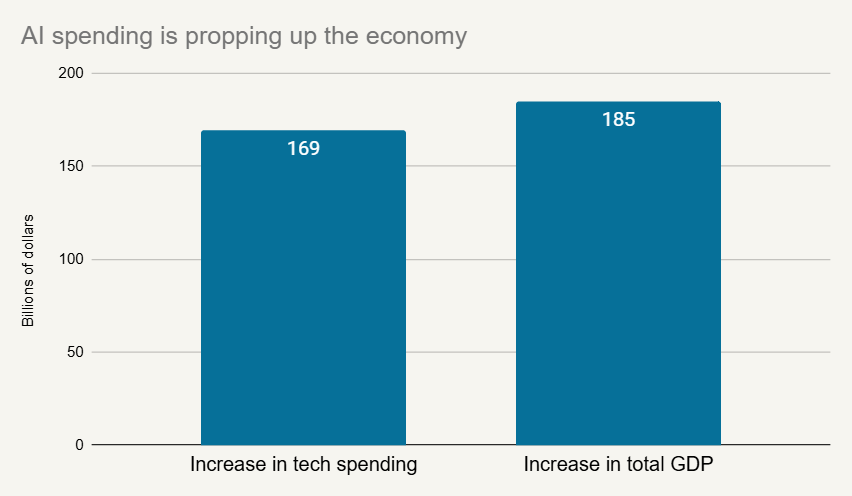

Currently the economy is being propped up by AI spending. This is something Harvard economist Jason Furman among others have written about. If we look at the components of U.S. GDP in 2Q 2025 vs. the end of 2024, total GDP has grown by $185 billion on an inflation-adjusted basis.

If we look at the underlying components of total spending, you can isolate the areas where AI spending would show up. There is a category called “fixed investment” where all construction, equipment, and “intellectual property” spending goes. Within that category, we can further isolate it to “information processing equipment” and “software.” Logically AI spending would mostly fall into one of those two categories. So far in 2025, that total tech spending has risen over $169 billion.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

This means that if we took out all growth in tech spending, which has probably mostly been driven by AI spending, GDP wouldn’t have grown at all so far in 2025.

How sustainable is this? It has definitely happened in the past where some parts of the economy kept growing while others contracted. In fact, many argue there have been “rolling recessions” since 2021, where individual industries have contracted, but this was offset by growth in other segments. A few times these were large enough to produce a near zero or even negative quarter for overall GDP growth, but never an actual recession.

So it could be that we’re currently going through one of those lull periods. Maybe the effect of tariffs is enough to cause many parts of the economy to slow down, but this is being offset by huge growth in AI spending. For that to be sustainable though, the rest of the economy needs to also resume growing before too long.

One of the key reasons these “rolling recessions” never turned into a broader slowdown was strength in consumer spending. Without reasonably strong employment growth, consumer spending will probably stagnate. If that happens, AI spending won’t be enough to prevent a recession.

Fed cuts likely to continue into 2026

Powell did not commit to any specific action in future meetings. In fact, he went out of his way to say that “there were strongly differering views” within the Fed committee about what action to take in December, and that a rate cut is “not a foregone conclusion.” However, Powell also emphasized that the “balance of risks” was toward weaker employment. I think it is unlikely that changes between now and December. It would take a big surprise to the upside either in jobs or inflation to change the course.

What happens after that depends on the economy. I would expect the Fed to keep cutting roughly every meeting in 2026 until there is some rebound in employment. Right now job growth is only slightly positive, but the Fed knows that slightly positive isn’t good enough. Certainly if job growth turns negative, we could see the Fed get even more aggressive with cuts.

It is possible that inflation pressures force the Fed to pause hiking rates. Earlier I mentioned that Powell was unusually forceful in saying that no decision has been made about the December meeting as of yet. It is possible that this statement was part of a compromise. Perhaps some Fed officials were uncomfortable with cutting rates today, and wanted the public to hear that further cuts were not a “foregone conclusion.”

Specifically, there are some, including Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic, who argue that very low immigration levels mean that the economy may not be able to add a lot of new jobs. I.e., there aren’t enough workers to allow for rapid job growth. Powell called this a “curious balance” within the labor market: demand for workers seems to have dropped substantially in 2025, but this has happened at the same time that supply of workers has also declined.

If this is true, Fed rate cuts could just cause the labor market to get extremely tight, which was a major cause of inflation in 2021-2023.

However I doubt that’s a problem we see crop up until at least 1Q 2026. For now, the Fed is focused on weakness in the labor market, and that makes more rate cuts extremely likely.