Facet’s Investment Management Program

Philosophy, Strategy, and Implementation

Introduction

Our investment approach is designed to maximize our clients’ chances of reaching their objectives. Whether that is planning for education, retirement, a large purchase, or building generational wealth, everything we do is guided by our foundational principles.

Our Beliefs and Core Principles

Every decision we make is governed by a strict set of guidelines. Our investment philosophy influences these core principles, and focuses on strategies that help our clients generate and keep more.

We Plan For Our Clients’ Ever-Evolving Lives

Our belief is that the best investment strategy should be linked to an ongoing financial planning approach that covers a client’s entire life. These constantly evolving plans ensure no money is left on the table as our clients’ lives change over time.

We Invest as a Team

We take an institutional approach to investing, the same core process that large institutions, such as university endowments, pension funds, and foundations utilize in building portfolios. This method allows us to avoid mistakes—with decisions made by consensus—always vetted by our Investment Committee.

We Avoid Forecasting

Decades of research on market efficiency indicate that forecasting the economy or individual stocks does not produce consistent results. This is why we believe in optimizing the risk/reward within our portfolios in any given environment. This means we will own more assets with a favorable risk/reward balance and fewer (or none) of less favorable assets.

This is distinct from optimizing based on a forecast, where portfolios are either “right” or “wrong,” depending on a future outcome. As a result, our portfolios are not static but evolve based on current circumstances.

We Invest for the Long Term

We utilize investment classes that generally go up over the long term (positive drift). We do not invest in highly speculative investments or investments that require market timing or stock picking. These investment methods have been proven to put investors at a disadvantage.

We Price Our Service For Ongoing Alignment

Our flat fee structure offers superior value by linking investing to the rest of a client’s ongoing planning effort at no additional cost. Compared to the AUM-based fee model (assets under management), we do not profit from the assets we manage. This reduces potential conflicts of interest and ensures that our clients’ assets reflect their financial intentions and values.

Part One: Drivers of Our Scientific Approach

Our investment approach is based on the academic science of financial theory. The result is a program that draws from peer-reviewed and time-tested scientific research of Nobel Laureates1 and incorporates up-to-date innovations from industry leaders.

This approach allows us to take advantage of the things we can control, like low fees, tax efficiency, broad diversification, and staying fully invested. These factors have been scientifically proven to provide investors with an advantage when compared to other investment methods.

This research has led us to a portfolio that utilizes a mix of exchange-traded funds (ETFs). This strategy provides broad diversification while maximizing risk/reward for a given environment.

Markets are Inherently Efficient

The Efficient Market Hypothesis is a cornerstone of all modern financial theory. The concept is that the market reflects all available information at a given time. Awarded the Nobel Prize, Eugene Fama, Harry Markowitz, Merton Miller, and William Sharpe were pioneers of this and other related concepts.

The logic behind this idea starts with the fact that for markets to settle on a price, buyers and sellers must agree on a suitable price for a security. As new information about that security becomes available, millions of diverse investors immediately act upon that information, rapidly driving the price toward a new fair value. The price will not settle too low, or investors will buy the stock until it rises, and vice versa. This is what we mean by the market being “efficient.” The price fully reflects the collective opinions of millions of investors with access to the same information.

Active Management Challenges

An active manager is an investor who selects stocks they expect to perform better than the general market. To be an active manager attempting to identify undervalued securities, one must believe they have information not already reflected in the prices. Moreover, one must also believe they can do better than all other market participants analyzing the same information. Additionally, they must do this successfully over and over in order to build an outperforming portfolio.

Unfortunately, evidence shows that this kind of skill is rare, if it exists at all. For example, in the ten years ending June 30, 2022, less than 10% of all US large cap funds outperformed the S&P 500 after accounting for fees. Moreover, there is similar poor performance across various time frames or segments of the equity market.

If anything, markets have become more efficient since the early Efficient Market Hypothesis research in the 1970s. Information now travels much faster since the dawn of the internet. Computer algorithms are trained to trade on momentary market anomalies within milliseconds. In addition, new kinds of data—like real-time credit card data, search engine activity, and social media sentiment—have made it even harder to have an informational edge over other participants in the market.

This is not to say that markets are always perfectly efficient. Many argue that price bubbles are an example of markets being inefficient, such as the internet bubble of the late 90s or the housing bubble leading up to the 2008 Financial Crisis. These are cases where, at least in hindsight, markets seemed to price in a degree of optimism that was unrealistic.

Nevertheless, we believe markets are generally efficient—and when they are not—they are typically hard to predict. Therefore, consistent but not necessarily static market exposure tends to produce the best results.

Market Timing Challenges

It is understandable why investors find market timing so tempting. If one could avoid down markets and only invest during good times, large returns would follow. However, the data shows that trying to time the market is extremely hard and does more harm than good. This is mainly because of the points we made about market efficiency. In order to time the market, one would need more information than all other market participants. It is extremely difficult to get such an edge consistently.

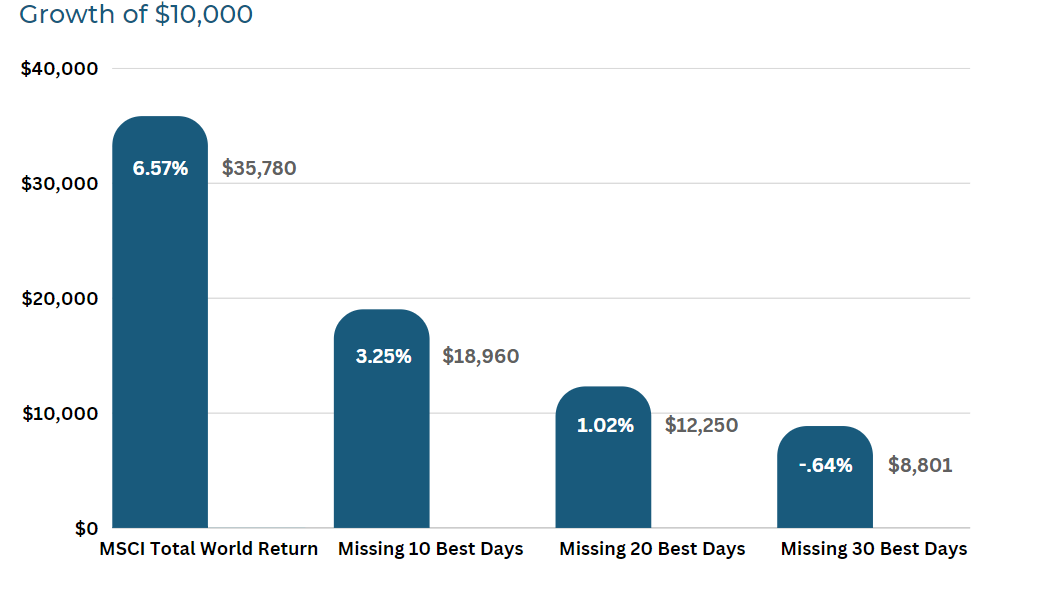

A good illustration of the futility of market timing is to look at how the best and worst days in the market have contributed to overall returns over extended periods of time. For example, using a broad developed market index (the MSCI World Index), the global stock market has returned about 6.57% per year for the 20 years between 2001-2020. So, an investment of $10,000 in the market for those 20 years would be worth around $36,000 by the end2.

However, if that investor missed the ten best days of the market, their annual return would have only been around 3.25%, and the value of their investment would have been around $19,000. If they missed 20 days, their return drops to 1.02% and their investment value sinks to $12,250. Finally, if they missed 30 days, the investor would have lost money.

Exhibit 1: Impact of Missing the Best Days During Down Markets

Another challenge of market timing is that it requires two decisions: when to sell and buy back into the market. It is very hard to time the market right once, let alone twice. Even if one sells early in a market collapse, this benefit can be destroyed by getting back into the market too late, especially because market recoveries are often fast and aggressive on the way up.

When stocks fall, it is not just a declining outlook causing the drop. The uncertainty about the outlook itself also weighs on stock prices. Generally, all that needs to happen for stocks to rebound is for conditions to improve somewhat. Sometimes not even an improvement in market conditions causes stocks to rebound. However, the outlook becomes a little clearer. Selling stocks at the end of the 2008 “Great Recession,” when the economy looked grim, is a good example of this point.

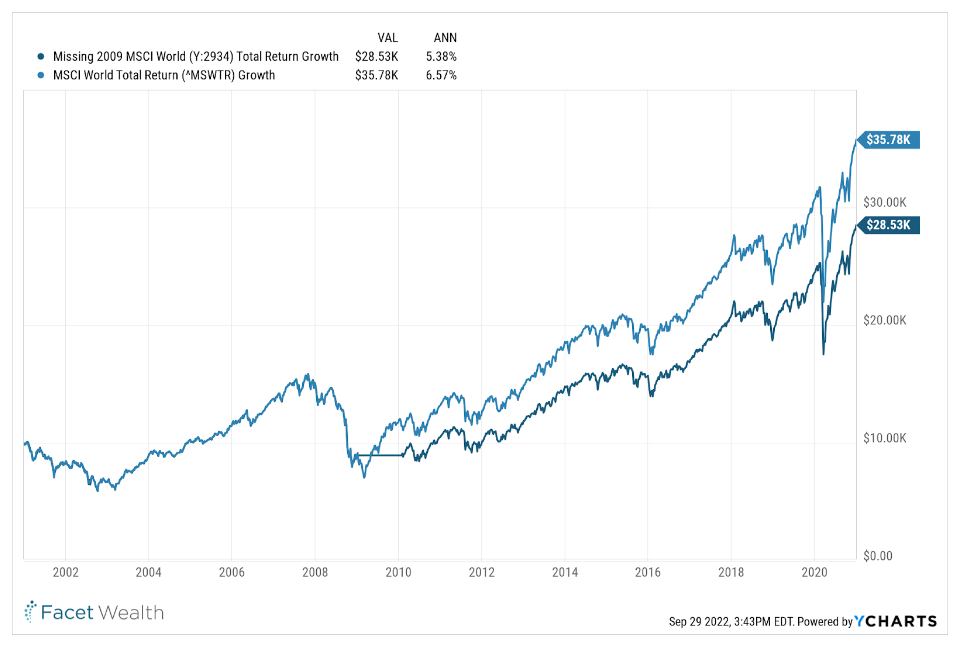

For example, if an investor got out of the market at the end of 2008 and didn’t return until 2010, their return would be much lower than if they had remained invested throughout the entire period. In this case, their 20-year return would have been a full 1% per year lower than if they had stayed invested. This market timer’s $10,000 investment would be worth $28,000 instead of nearly $36k3.

Exhibit 2: Impact of Selling at the End of the Great Recession

Note that the market bottom in 2009 happened well before the economy started to truly improve. After stocks bottomed, subprime foreclosure rates kept rising for nine more months, and home prices did not hit bottom for two more years. Similarly, in 2020, when the market bottomed, the discovery of a COVID vaccine was eight months away. In both examples, we see that markets bottomed and improved not when the bad news stopped coming but when there was less uncertainty overall.

Forecasting Challenges

Previously we discussed market efficiency in the context of individual securities, but the same idea applies to macroeconomic research. For example, investors constantly try to predict the odds of a recession or the inflation rate, and these estimates get incorporated into market prices. In other words, market prices reflect the consensus forecasts for the macroeconomy.

If one uses macro forecasts to make investment decisions, this presents two problems: First, the macroeconomics is highly complex, and getting any specific forecast right is extremely difficult. Second, since market prices reflect the best thinking of all market participants, to successfully invest based on one’s own forecasts, one must presume they can consistently outsmart thousands of other investors. Evidence shows that few investors, if any, achieve this consistently.

We can show this by looking at the public record of economist forecasts. The Philadelphia Federal Reserve tracks the Survey of Professional Forecasters with data dating back to 1968. What we see is that accurately predicting the kinds of things that would matter to investors is extremely difficult.

For example, the survey asks forecasters to estimate the chance that the US Gross Domestic Product will be negative in the subsequent year. Effectively this is the forecaster’s odds of a future recession. Since 1968 there have been seven non-overlapping occasions where GDP went negative for a 12-month period. The forecasters collectively predicted none of them. On average, in the year prior to the decline in GDP, the mean forecasted odds of a GDP decline was 22%. The closest they came was in 1979, with a predicted 36% odds of negative GDP the following year.

This is not because these economists are inept but rather because forecasting is difficult. The economy has many variables, and those variables interact with each other in different ways depending on the circumstances. Unexpected events can emerge overnight and ultimately have a significant impact on the markets. Two such recent examples are the COVID pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Managing Biases

We operate in the same way as institutional investors. Central to this overall approach is the idea that avoiding mistakes is a major key to successful investing. Since biases often have an effect on decision making, they commonly lead to critical errors.

Unfortunately, the biggest enemy in making consistent, disciplined decisions is ourselves. The field of Behavioral Economics studies how various biases exist in all of us and can tend to result in suboptimal decision making.

There are several different types of biases that can affect decision making. Human biases are considered unintentional, because they often occur unconsciously. Intentional biases, on the other hand, are made when someone takes action deliberately.

Let’s explore these common biases in more detail.

Human Biases

Prospect theory: States that humans tend to put too much weight on improbable events. In markets, this sometimes causes investors to chase big returns in highly speculative investments.

Self-serving bias: The tendency of people to take personal credit for good outcomes but blame bad luck on negative outcomes. So, for example, a stock picker might credit shrewd analysis for winning picks while blaming outside forces for losers. This is probably a big reason people keep trying to pick stocks despite the overwhelming evidence that it is ineffective.

Herd behavior: Causes people to crowd into popular investments, often at the wrong times. This bias explains why bubbles keep forming in various corners of financial markets.

These biases are common in all of us, even highly experienced professionals. Facet’s investment team is no exception.

Intentional Biases

There is a special bias called relative performance bias that exists in the investment management industry. Most investment management firms sell their services largely on performance.

Portfolio managers try to outperform some benchmark, and then the firm touts that performance as evidence of their expertise. The implied claim is that past outperformance denotes a persistent skill that will result in future success.

Earlier, we discussed how stock picking and market timing seldom lead to outperformance. This need for outperformance creates another problem, however. That is, firms will seek outperformance even at the expense of undue risk.

Any degree of underperformance results in new product sales plunging. So managers often think 1% or 5% underperformance is essentially the same. They would rather risk a 5% underperformance for a shot at 2% outperformance.

We believe this creates a misalignment of incentives. In this case, portfolio decisions are not made based on the client’s priorities or a balance of risk/reward but rather on the business incentives of the firm.

To manage the influences mentioned previously, we employ a strict set of rules that keep our decision-making objectively aligned with our core principles.

- We follow a rigid and documented process. When considering a portfolio change, we require a detailed set of items to be researched and completed. While this takes considerable time and effort, it helps ensure decisions are made for objective reasons.

- All decisions are made as a team. Because we view avoiding mistakes as paramount, all portfolio changes are vetted by our Investment Committee, with decisions only made by way of consensus. If an idea is not strong enough to garner the entire Committee’s buy-in, we do not execute on it.

- Our decisions are about risk/reward, not about being right. We do not sell performance alone, so there is no incentive to take undue risks. All our decisions are with the client’s best interests in mind.

- We focus on long-term results. When we make changes to our portfolios, we intend to remain in the new position for an extended period. We are not short-term traders.

Part Two: Portfolio Construction

Guiding Principles That Drive Portfolio Creation

At Facet, we start with a client’s priorities before making any investment decisions. From there, we can determine the right time horizon, return objectives, and risk tolerance. Unless these factors are well-defined, any investment program is incomplete.

The investment management business is generally structured around maximizing performance against a benchmark. We believe this approach is problematic since no one’s financial plans have anything to do with beating a benchmark. Ultimately, clients are concerned with meeting their objectives, such as paying for college or funding retirement. These priorities, along with several others, are our main focus when structuring our portfolios.

Core Portfolio

In the prior section, we discussed the challenges of active stock picking, market timing, and forecasting. In addition, we discussed the advantages of low fees and broad diversification. Because of all of these factors, our portfolios are built out of a set of low-cost ETFs.

How We Monitor and Rebalance Portfolios

Our portfolios are not static; rather, we adjust our mix of holdings to maximize risk/reward in a given environment. Earlier, we said that markets are generally efficient, and when they are not, they are generally unpredictable. For this reason, we do not believe anyone can consistently out-forecast the rest of the market. However, there are times when market risks are unbalanced.

For example, an asset class performs similarly to other assets in one scenario but significantly underperforms in another. Alternatively, the asset does very well in one scenario and about the same as other assets in another.

While this only happens occasionally, we want to take advantage when it does. We will overweight assets that are imbalanced in our favor and underweight those that are imbalanced against us. Note that this approach does not require us to know which scenario is more likely, but merely that the outcomes are imbalanced. One specific example was our elimination of international bonds in 2022.

At the time, US bonds had more yield than their non-US counterparts, which suggests that US bonds have a higher expected return. In addition, we felt that the risk of credit stress in European government bonds was not reflected in those yields, particularly given the recession risk in Europe.

To be clear, we did not predict a recession in Europe or that a recession would bring stress to government bonds there. Instead, we felt the risk/reward was imbalanced. US bonds would probably outperform mildly—given their higher yield if nothing happened—while international bonds would underperform significantly if government bonds came under stress.

This example shows what we mean by optimizing for risk/reward. While these opportunities do not always exist in a given period, when we find them we have the flexibility to take advantage of them.

How We Maximize Portfolio Gains

Taxes can put a damper on the actual returns of an investment portfolio. We aim to minimize this impact to maximize what returns our clients keep. This is accomplished using three different tools: index-based ETFs, tax-loss harvesting, and planning strategies.

Index-based ETFs

By law, mutual funds must distribute any realized capital gains to investors. Effectively, this means an investor can realize a tax event on their fund holding even if they do not sell the fund.

Facet utilizes index funds that naturally have lower turnover. More importantly, structural differences between ETFs and mutual funds help ETFs avoid capital gains distributions. As of June 30, 2022, none of the ETFs in Facet’s recommendation list had made a capital gains distribution in the last ten years.

Tax Loss Harvesting

Tax loss harvesting is when an investor realizes a loss for tax purposes but does not significantly change their investment portfolio. There is some complexity to how it works, but here is an example.

An investor bought $10,000 worth of XYZ investment in January 2022. By March 2022, the investor’s $10,000 investment lost 20% of its value and was worth $8k. Without a tax loss harvesting program, this investor would stay the course and hold the investment. However, we can do more than just stay the course by selling XYZ investment and immediately buying a similar but substantially different investment, ABC Investment.

Both ABC and XYZ investments have similar investment styles, so the overall investment philosophy stays the same. However, they differ enough not to trigger a wash sale. With this transaction, we were able to keep the investor invested for a potential market recovery, and we were able to give the investor a $2,000 capital loss, which they can use to offset a current or future capital gain or offset their ordinary income.

This transaction alone could save an investor in the 24% tax bracket up to $300 in capital gains or $480 in ordinary income taxes. That is 3-6% of the now $8,000 portfolio, a huge benefit.

Tax loss harvesting is a big benefit when used appropriately. However, there are trade-offs. We designed our process to maximize the benefits vs. the trade-offs.

These trade-offs include:

- “Wash sales”: A wash sale occurs when a tax loss is disallowed because an investment deemed too similar was purchased in too short of a horizon from the original sale. Overly frequent tax-loss sales increase the risk of wash sales.

- Sub-optimal replacement investment: The benefit can be reduced if the investor harvests their losses into a suboptimal investment. For example: the investor buys a fund with a higher expense ratio. We mitigate this risk by minimizing the frequency of times we harvest losses. I.e., making tax sales every time there is a small loss can result in one eventually holding their 10th best investment.

- Lower cost basis: There is a trade-off involved in tax-loss harvesting. Effectively, tax-loss harvesting defers an investor’s capital gains into the future. Each time someone harvests losses, they are lowering their cost basis.

In the example above, the cost basis went from $10,000 to $8,000. If the investment goes to $20,000, the investor will have a $12,000 gain instead of the $10,000 they would have had without harvesting the losses.

If an investor moves to a higher tax bracket (e.g., during a distribution phase), their taxes might increase. In such a case, we mitigate this risk by not harvesting their losses.

Planning Strategies

By combining planning strategies with investments, Facet can further help mitigate the tax impact of an investor’s portfolio. This includes utilizing tax-advantaged accounts, such as 401(k)s or IRAs, and particularly being intentional about what assets go into these accounts vs. fully taxable accounts. Other strategies may include using municipal bond funds, stock gifting, or management of low-basis holdings, to name a few. Of course, using these tools greatly depends on one’s particular priorities and tax situation, which is a major advantage of our planning-based approach.

Commitment to Continual Improvement

Facet’s investment approach is based on some simple ideas: start with a purpose, optimize for risk/reward, make decisions in a consistent and disciplined manner, and avoid common mistakes. We believe that getting these basic things right will lead to superior results, and this belief is backed up by much of the research presented in this paper.