The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Stagflation is a period where both inflation and unemployment are high.

- Stagflation is caused by sudden decreases in the supply of goods and services, something that tariffs could in theory bring about.

- Stagflation creates major problems for the Federal Reserve, as they must choose to either fight high inflation or high unemployment.

- The U.S. has some natural protections against tariffs having a large impact, including a relatively small trade sector compared to a large services sector.

Stagflation is the worst of all worlds economically: it is a period where inflation is high and unemployment is rising simultaneously. Stagflation is extremely rare. It hasn’t happened in the U.S. in any real way in almost fifty years. Unfortunately, rising tariffs is one of the few possible triggers for stagflation. Here are our thoughts on what stagflation is, and what the threat might be today.

What is “stagflation”

The term “stagflation” was coined in the U.K. in the 1960’s to describe a period of weak economic growth and high inflation. It is a mashup of the words “stagnant,” i.e., a listless economy, and “inflation” i.e., rising prices.

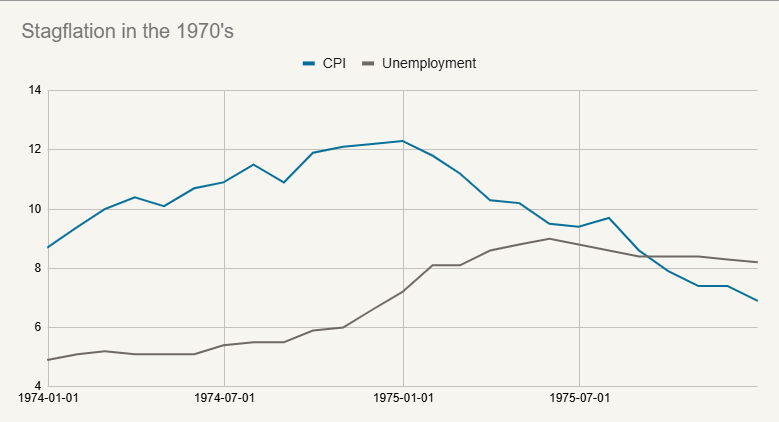

In the U.S. the term is most often used to describe the mid 1970’s. During 1974 and 1975, unemployment rose from 4.9% to 9.0% while inflation rose as high as 12.3%.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

There is a reason why stagflation has not occurred since that period: under normal economic conditions high unemployment tends to cause inflation to fall. That’s because high inflation is caused by consumer spending outpacing the economy’s ability to produce. In other words, consumers have more money to spend than firms have goods to sell.

Rapid consumer spending is almost always the result of rapid income growth. This is only going to happen if job growth is strong. Hence why, under normal circumstances, inflation is only high when the economy is booming.

Stagflation requires a “supply shock”

It is possible for inflation to occur for a different reason. Imagine a scenario where consumer spending stayed steady but production declined. I.e., consumption is still outpacing production, but it is because production is falling not because consumption is rising.

This is how you can get stagflation. Remember that economic growth is just another word for growth of production. If the economy is producing less goods and services, you have the “stag” part of stagflation. If consumer spending stays high enough relative to production, prices rise. Hence, the “flation” part is fulfilled as well.

This is what economics call a “supply shock.” Something that happens suddenly to cause the supply of goods and services to contract. In the 1970’s it was mainly an oil embargo that provided the supply shock. This caused the cost of production to increase suddenly and rapidly.

When the cost of production rises, companies either raise prices, produce less, or both. The sudden lurch higher in oil prices had just this effect. The economy contracted and firms laid people off. Firms also raised prices, content to sell fewer goods at higher prices.

Tariffs could have this same effect

The sudden imposition of tariffs could also create this “supply shock” effect. It directly causes the price of imported goods to go up. It probably also causes the supply of imported goods to go down, as international firms will be less willing to sell goods into the U.S. market.

In addition, most domestically produced items will have some parts or raw materials, which means the price of production is going up on those goods. Lastly, the non-U.S. firms that exit the U.S. market were likely lower cost producers compared to domestic firms. This is what economists call “comparative advantage.” This effect too will drive up prices.

So here we have at least a plausible scenario where stagflation could be possible. Tariffs raise prices and lower production. If the effects are large enough, that could indeed lead to stagflation.

To me the question is whether these effects are large enough to actually produce something like a stagflation effect.

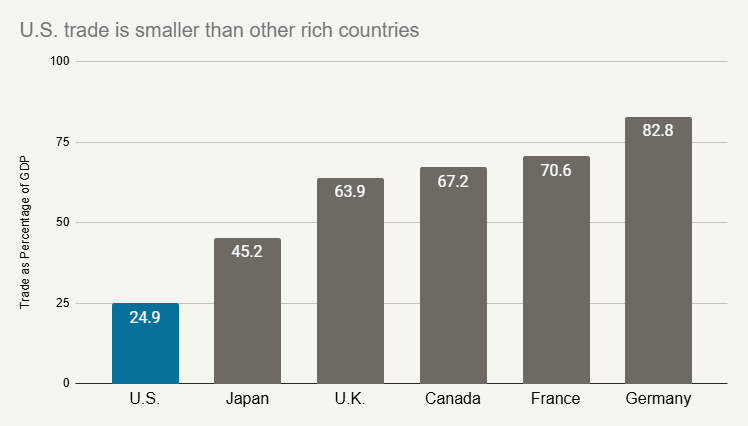

Trade as a percentage of the U.S. economy, defined as imports plus exports, is only about 25%. Which means 75% of our economy is produced and consumed entirely within our borders. This is by far the highest percentage among rich countries.

Source: World Bank

Now one reason for this is that the U.S. is just so large. Other wealthier countries, like the U.K. or Germany or Japan have to trade a lot more just due to their size.

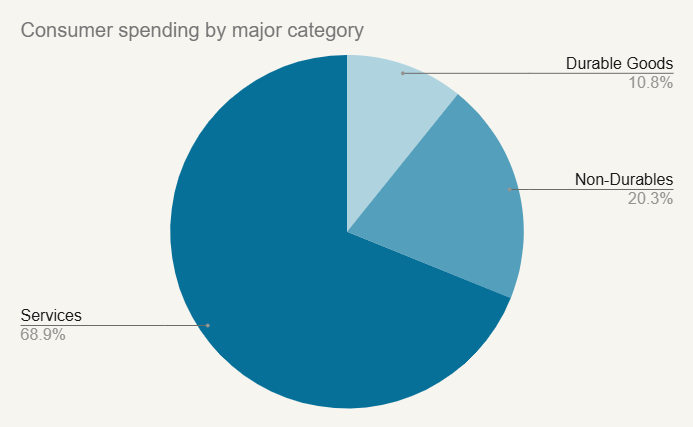

The other reason why trade is relatively small is because the U.S. is primarily a services-based economy. Consumer spending is about 69% services, and only about 11% of what’s called “durable goods.” This is any physical good that is not immediately consumed. It includes everything from iPhones to automobiles, and this makes up the bulk of goods the U.S. imports.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

This means there is a relatively small segment of the economy that is heavily impacted by tariffs. Given this segment is so small, it would take a very large impact on that small subset of goods to get either a big shift in inflation or a contraction of economic growth.

Stagflation and the Fed

One reason why stagflation is such a problem is that it puts the Federal Reserve in a bind. Legally the Fed has two mandates: to keep prices stable and promote full employment. Most of the time these goals are not in conflict, but with stagflation they would be. The Fed would have to choose which of the two mandates to make worse in hopes of solving the other.

We believe it is likely the Fed would choose to fight inflation first if it really came to it. However, it may not be that straightforward.

Both Fed Chair Jerome Powell and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent have said that the inflation impact of tariffs may be “transitory.” That is to say, it might be that tariffs cause a one-time increase in prices, but not necessarily an inflation rate that remains high thereafter. If this is the case, the Fed would be likely to cut rates if tariffs seem to be causing a weak economy.

There are risks to tariffs, but stagflation remains a long way off

Tariffs do pose some unique risks to the economy. We have written a few times that tariffs are not a good policy. The directional impact of tariffs is to lower growth and increase prices. In other words, we believe that widespread tariffs would make U.S. growth lower and prices higher in 2025 than it would have been otherwise.

However, we should emphasize “would have been otherwise” is the key there. The U.S. economy came into 2025 with a lot of momentum. In addition, the most recent data points to inflation easing.

Could tariffs reverse all of that positive momentum? Possibly. However we think tariffs alone probably are not enough. It will probably take multiple negative effects to actually drive economic growth weaker or inflation materially higher.