Key takeaways

- The underlying economy is much stronger now than in 2008. Back then, the US was already in a recession, and unemployment and mortgage delinquencies were high

- Unlike in 2008, banking losses today primarily come from rising interest rates rather than bad loans

- Banks are significantly less leveraged than they were in 2008

- Liquidity problems can still cause banks to fail, but the Federal Reserve is better equipped to deal with them now

- Banks may become more conservative by lending less and hoarding cash which could lead to slower consumer spending and a reduction in inflation

For many investors, the sudden collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse has evoked bad memories of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. However, these two banking crises are anything but the same.

While today’s banking stress is severe and could have meaningful economic consequences, it is a very different situation from 2008. The only thing 2008 and 2023 have in common is that banks are the main focus.

Here are our thoughts about why the two situations are different and what that tells us about how today’s banking stress might play out.

The underlying economy is strong now, but it was weak in 2008

When Lehman Brothers failed in September of 2008, the US economy had already been in recession for nine months.

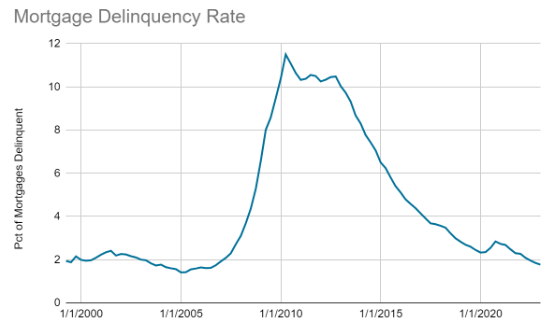

Unemployment had already risen from 4.4% to 6.1%. Home mortgage delinquencies were already at an all-time high (and continued going higher). In short, a very fragile economy caused the banking system’s stress.

On the other hand, today’s economy is robust. In fact, until now, the biggest concern has been that the economy was too strong, with solid wage gains and consumer spending boosting inflation.

As a result, economic indicators like unemployment and mortgage delinquencies are close to all-time lows, while consumer spending and job growth are running at above-average growth rates.

Today’s banking losses stem from interest rates, not credit

Ironically, today’s economic strength is indirectly causing stress at banks. For example, according to its most recent quarterly report, Silicon Valley Bank’s percentage of non-performing loans (i.e., any loan that isn’t current on its payments) was only 0.18% of its total loans.

By comparison, at the largest traditional bank to fail in 2008, Washington Mutual, 4.67% of its total loans were not performing the quarter before they were shut down.

Today’s bank losses don’t stem from bad loans but from rising interest rates. Most banks own large portfolios of government bonds, such as Treasury bonds or government-backed mortgage bonds. So when interest rates rose substantially in 2022, the price of these bonds declined.

Banks usually don’t have to realize these losses on their accounting books until they sell the bonds. Generally speaking, the only reason banks would sell is if enough deposits left the bank, it would have to liquidate to make its depositors whole.

Unfortunately, this scenario is precisely what happened to Silicon Valley Bank. The bad news is that just about all banks are sitting on some amount of these interest-rate-related losses. The good news is that we know exactly how large these losses are. That’s because banks must report the unrealized losses on their bond holdings each quarter.

Moreover, these holdings are relatively easy to value. But, again, they are overwhelmingly government-backed bonds that trade daily, so determining these securities’ current market value is straightforward.

This was in contrast to 2008, when many banks had hidden losses in derivatives or hard-to-value securities. This made it unclear how exposed any given bank was to subprime mortgage losses.

Additionally, no one knew how bad losses in the housing market would get. As banks foreclosed on more houses, more and more houses went up for sale. As more houses entered the market, home prices plummeted, making bank losses all the worse.

In 2008, there was no obvious way to arrest this downward spiral. This was what caused such fear about banks at that time. Today there’s nothing comparable going on. To that end, there’s no reason for bank losses to spiral downward similarly.

There is far less leverage in the banking system

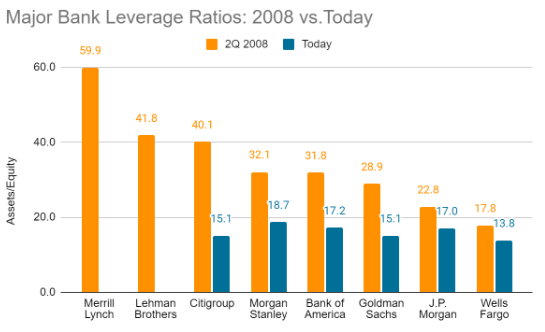

Another significant change is how much less leveraged the banking system is as a whole.

A bank’s assets include things like investments and loans. It can pay for those assets by either using its own money (equity) or borrowing that money from someone else, which includes depositors or other kinds of borrowing.

The more a bank uses its own capital, the more it can weather investment losses and depositor withdrawals.

The chart below shows the ratio between assets and equity of the largest US banks in June 2008 vs. today. This ratio displays each bank’s asset values held per $1 of equity. Lower numbers mean less leverage, which indicates the bank is more able to handle losses without going out of business.

Data sourced from Bloomberg

Here we see that every one of the big banks has greatly decreased its leverage.

In some ways, this probably understates how big of a change banks have made over this period. Before 2008, banks heavily used derivatives contracts to make bets on various parts of the market. These contracts often had embedded leverage that wouldn’t appear in a bank’s official books.

At that time, banks could also use so-called “off-balance sheet vehicles,” allowing them to make leveraged bets that didn’t clearly appear on their accounting statements.

Fortunately, regulators have banned or significantly curtailed all those practices since then. What is left is a banking industry that is much more boring but also a lot safer.

Liquidity problems are easier to solve but will still have an impact

The challenges banks face today are the same problems they have struggled with for centuries: no bank can survive if too many depositors demand their money at the same time. You may remember the plot of Mary Poppins and It’s a Wonderful Life feature this exact problem.

Silicon Valley Bank lost approximately $15 billion on its government-backed bond portfolio. If none of its clients had withdrawn deposits, it could have just held on to those bonds until they matured. Then, everything would have been fine.

However, once withdrawals reached a critical point, it was forced to sell some of those assets and realize these losses. Once that happened, the SVB fell below certain regulatory requirements, which triggered the FDIC to shut the bank down.

Because Silicon Valley Bank decided to own more long-term bonds than just about any other bank, they were especially vulnerable to this series of events. However, if enough clients pull their deposits, this could happen to any bank.

The good news is that it is much easier for the Federal Reserve to deal with a bank suffering liquidity problems vs. one suffering credit losses.

Already the Fed has created a new lending facility called the Bank Term Funding Program, which allows banks to borrow cash by pledging government bonds as collateral. Of course, the bank still is on the hook for loss if they eventually sell the bond, but this allows the bank to get cash temporarily to meet customer requests as they arise.

This is one of the reasons why we think officials will likely be able to contain this banking crisis and prevent widespread bank failures. However, that does not mean there won’t be consequences from this period of bank stress.

Bank managers will want their institution to avoid suffering the same fate as Silicon Valley Bank. To ward this off, we expect banks to become more conservative, specifically by lending less and building up a larger cash balance. Regulators may also encourage this same thing.

Less bank lending means less money for companies to spend on things like new construction or expanding their business. That’s why when banks pull back on lending, it tends to result in less hiring, which will probably cause consumer spending to slow down.

Interestingly, this could be a positive: If businesses and consumers spend less, it may finally solve our inflation problem. The Fed has wanted some degree of an economic slowdown for several months but has been unable to get it through rate hikes. So it could be that this banking stress finally delivers what the Fed couldn’t do on its own.

Whether this turns into a recession or merely enough of a slowdown to reduce inflation remains to be seen. Regardless, there’s really no comparison between what we see with banks today and the crisis that unfolded in 2008.

Tom Graff, Chief Investment Officer

Facet Wealth, Inc. (“Facet”) is an SEC registered investment adviser headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland. This is not an offer to sell securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This is not investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.