The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- Delaying paying taxes on investments in a taxable account allows for compounding to work in your favor and can potentially lead to better returns

- Reallocation to a better portfolio may lead to some tax consequences but is generally worth it in the long run depending on the account type

- Diversifying a concentrated portfolio sooner is better than later as it may reduce the risk of losing money

- Tax-loss harvesting may be useful for lowering tax burdens but should not negatively impact the portfolio

- Planning and investing should go hand in hand to maximize after-tax results rather than just minimize taxes

No one likes paying taxes.

According to a recent Pew Research survey, 71% of Americans are frustrated with how much they pay in taxes, and 85% are frustrated with how complicated taxes are.

Unfortunately, if you are making money in your investments in a taxable account, you’ll probably wind up paying at least some taxes on those gains. And the impact of those taxes on your portfolio can be quite complex.

While some basic rules for managing taxes well exist, the right strategy greatly depends on your personal circumstances.

Here are a few ideas on how to factor taxes into your investment decisions.

You can’t avoid taxes, but you can delay

The first thing to remember is that there is only one way to avoid paying any tax on your investments: continuously lose money. Since no one wants that, you should approach investing with the expectation that you will pay taxes on gains in your portfolio.

What you can do is delay paying taxes. This is important because of the effect of compounding. If you pay taxes on your gains now, that leaves you with less money invested in the market. Since stocks and bonds tend to rise over time, the more you have in the market, the better your returns will be, all else being equal.

Here’s an illustration of the point.

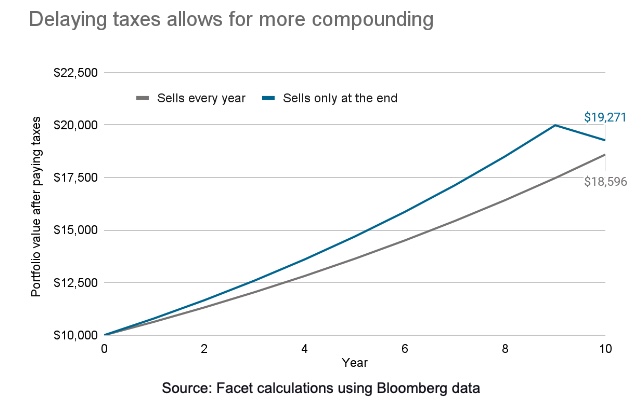

Say two investors put $10,000 into the market, both with a ten-year horizon, both in a taxable account.

The first one trades their portfolio every year and therefore realizes gains every year. (Note: investors only owe taxes on gains when a security is sold.)

The second leaves their portfolio alone and only sells at the end of the ten years.

Now assume both investors make 8% per year on their portfolios before considering taxes, and both pay 20% on their capital gains.

The chart shows the net of taxes portfolio value for both investors.

This chart highlights the power of compounding. The first investor (in gray) sold yearly and had to pay a small amount in taxes each time. That left them with slightly less money invested in the market.

Meanwhile, the investor in blue wound up owing a big tax bill at the end, reflected in the declining blue line in the last year. They had an $11,589 gain, which resulted in a $2,318 tax bill in the final year, for a net portfolio gain of $9,271. Still, this investor ended up with $676 more than the investor who paid their taxes each year.

Don’t let the tax tail wag the portfolio dog

This illustration above shows that all else being equal, delaying your security sales and tax bill can work in your favor.

But what if all else isn’t equal? At Facet, we often see members come to us with poorly allocated portfolios.

Sometimes they are in expensive mutual funds, undiversified accounts, or their risk tolerance is way off base. But moving such a portfolio to a better allocation might trigger significant tax consequences.

So what do you do in this situation?

Generally, the best advice is to reallocate to the right portfolio as quickly as possible, even if that means paying some tax now.

Here’s an example.

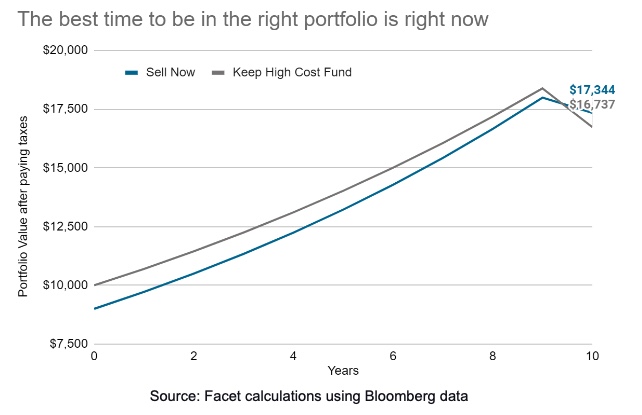

Assume two investors invested $5,000 several years ago, and their portfolios are now worth $10,000.

If they sell today, they would both owe $1,000 in taxes ($5,000 gain times the 20% capital gains tax rate).

However, let’s say these portfolios are in high-cost mutual funds. If they switched to lower-cost ETFs, they could save 1% in fees.

Now assume the first investor decides to bite the bullet and switch their portfolio today, while the second investor decides that saving on taxes is more important.

If they both received a market return of 8%, the high-fee investor is left with a 7% return looking forward.

Remember, in our first illustration, the investor who waited to sell and consequently delayed taxes had the advantage. But here, the investor with the less expensive portfolio, even while paying a big up-front tax bill, winds up ahead in the end.

Note that as the market continues to climb, the tax cost to switch portfolios also keeps increasing.

In the case above, both investors faced a $5,000 capital gain to switch at the beginning of this story. By year 3, the gain had grown to $7,250, and by year 5, $9,026.

Waiting to pay the tax doesn’t fix your portfolio problem; generally, it only results in paying more tax to make the shift.

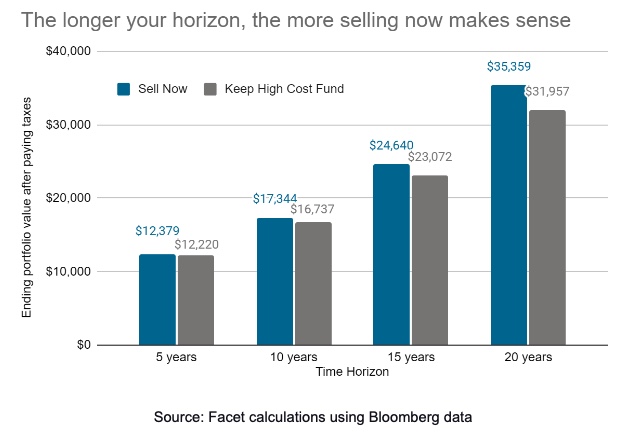

Also note that while we made this time horizon ten years, longer horizons would only tilt the analysis more in favor of acting now.

The chart below shows the same analysis as above but with a time horizon of 5, 10, 15, and 20 years. Here we see that the ending net-of-tax portfolio value is higher for the lower-cost portfolio in every instance.

The bottom line here is that delaying taxes is probably the right move when all else is equal. But if all else isn’t equal, you are usually better off transitioning to the better portfolio and paying any incurred taxes.

Note that this concept can also extend to more routine kinds of portfolio changes, such as rebalancing or making strategic shifts to a portfolio. Keeping your portfolio optimally allocated is usually worth paying some tax over time, especially since you would eventually wind up paying that tax anyway.

Taking the wrong risks

Another common transition situation is when an investor has an overly concentrated portfolio.

For example, maybe you have accumulated a large amount of stock from your employer. Or maybe your portfolio is dominated by a few individual companies. You probably know that diversifying will lower your risk, but is it worth paying the tax to do so?

This situation is slightly less obvious than the expense example above, but the conclusion is still the same: the sooner you get into the best portfolio, the better.

Consider that there are two possibilities for your concentrated portfolio. The first is that the stock keeps going up. If that happens, it will only get more expensive to diversify. You may as well do it sooner than later.

The other possibility is that the stock goes down (and could drop by a lot). Consider that in the last five years, just over half of the stocks in the S&P 500 have suffered at least a 50% drop at some point. The longer you hang on to a stock, the more likely you will suffer one of these devastating losses.

In some sense, this solves your tax problem, but your portfolio winds up worse off.

So if you wait, diversifying becomes more expensive, or your concentrated portfolio winds up losing money. Paying the tax now is usually your best course of action.

There certainly are situations where spreading out the tax burden makes sense. Depending on the situation, we often recommend transitioning portfolios in chunks over a period of two or three years.

In these situations, we use our own algorithm to determine what new investments will best diversify your old portfolio. Discussing this situation with your planner is the best way to determine the right solution.

Tax-loss harvesting: good if done right

Tax-loss harvesting is a strategy by which an investor realizes losses for tax purposes without materially changing their asset allocation. It can be a nice tool to lower your tax burden when used correctly.

However, the lessons above apply to tax-loss harvesting also. It isn’t worth doing if you will wind up with a worse portfolio in the process.

For example, selling a low-cost fund to buy a higher-cost fund just to realize a tax loss is a bad idea. This is because tax-loss harvest opportunities naturally occur during down markets, which tend to be volatile, often ending with large and sudden rebounds.

Given this, imagine you sold a good fund to realize a tax loss and bought a mediocre one with the proceeds. Then the market suddenly rebounds, and now you have a short-term gain in the inferior fund.

If you sell the mediocre fund to go back to the original fund, you will eliminate the benefit you got from the tax-loss harvest in the first place. On the other hand, if you keep the mediocre fund, you will wind up in the same situation we showed in prior sections, worse off for being in the wrong portfolio.

Facet’s approach to tax-loss harvesting takes this phenomenon into account. We calibrate our trigger points and fund selection to avoid putting our members in this situation. For more detail, see this article on our process.

Planning and investing go hand in hand

Taxes are a great example of why you cannot separate financial planning and investing. We have outlined a few examples of where managing taxes in your investment portfolio is tricky, but there are many others that depend on your goals and tax situation.

- Should you allocate your IRA or 401k differently than a taxable account?

- Should you own tax-exempt municipal bonds or taxable bonds?

- Which account should you use if you need to make a withdrawal?

At the end of the day, your goal should not be to minimize your taxes but to maximize your after-tax results. That requires being thoughtful about tax efficiency but keeping it in the context of your goals, situation, and portfolio allocation.

Tom Graff, Chief Investment Officer

Facet Wealth, Inc. (“Facet”) is an SEC registered investment adviser headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland. This is not an offer to sell securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This is not investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.