The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- The recent decline in the U.S. dollar's value in early 2025 is primarily due to global investors rebalancing portfolios away from previously overweight U.S. assets, not a fundamental rejection of the currency.

- Despite fluctuations, the U.S. dollar's position as the dominant global reserve currency is not under immediate threat, supported by deep U.S. financial markets and its widespread use in global trade.

- For U.S. investors, a weaker dollar can positively impact the value of their international stock and bond investments when converted back to U.S. dollars, providing a natural currency hedge.

- U.S.-based investors primarily face dollar-denominated expenses, making complex currency hedging largely unnecessary; a globally diversified investment portfolio offers adequate protection against currency fluctuations.

Recent headlines might have caught your eye: the U.S. dollar has weakened significantly in the early months of 2025. This often sparks conversations and concerns about whether the dollar is losing its long-held position as the world's dominant currency. For individual investors living and working in the U.S., what does this mean, and should you be worried?

While fluctuations happen, a closer look suggests that the dollar's fundamental role isn't under immediate threat, and the implications for U.S.-based investors are often different than perceived.

Why has the dollar declined?

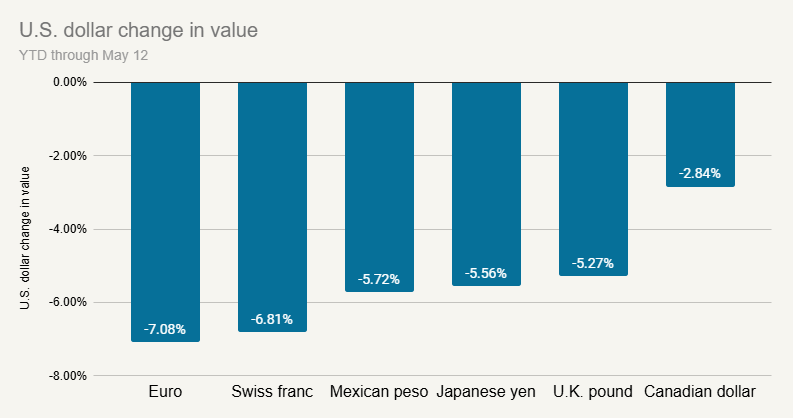

The threat of a trade war has certainly weighed on the dollar. At one point in late April, the dollar had lost more than 10% vs. the euro and the Japanese yen. It has recovered some value since then, but it's still down substantially vs. most major currencies in 2025.

Source: Bloomberg

However, this movement appears driven less by a fundamental rejection of the dollar and more by a rebalancing act from global investors. Coming into 2025, global investors were substantially overweight U.S. assets as a group. According to the closely followed Bank of America Global Fund Manager survey, 36% of global investors were overweight U.S. in December, the highest level in the survey’s history. By March that had completely flipped, with the average manager being 23% underweight U.S.

Why such a sudden change? Coming into 2025, the consensus was that the U.S. would be growing at a faster pace than other developed countries, and that U.S. stocks would keep getting a boost from the growth of artificial intelligence. Hence why so many were overweight the U.S.

Then President Donald Trump announced a much more severe tariff package than investors anticipated. This not only created a more uncertain economic outlook, but raised the risk that any slowdown would be focused on the U.S. Suddenly the global investors who were substantially overweight U.S. assets felt caught, and wanted to quickly diversify. We saw evidence of this in the Bank of America survey mentioned above, and it appears likely that continued into April.

Mechanically as investors move money from U.S. assets into other countries, that causes the dollar to decline. For example, if some pension fund sells shares in Microsoft and buys Nestle, this also involves exchanging dollars for Swiss francs. Hence when we saw this big shift away from U.S. stocks and bonds and into international assets, it only makes sense that the dollar would also decline.

The point here is that the recent move in the dollar is explained by basic economics, not by politics. There is a view that U.S. economic growth might be weaker than previously expected due to Trump’s tariffs. That caused a shift in allocations. This isn’t an abandonment of the dollar, rather a tactical shift by private investors.

Are governments abandoning the dollar?

To drive this point home, we aren’t seeing any evidence that governments have been selling dollars and/or U.S. Treasuries. Since Trump’s election foreign government holdings of U.S. Treasuries has been pretty steady between $3.8 and $3.9 trillion.

Source: U.S. Treasury

Unfortunately, this data is reported with a long lag, so February is the most recent figure that has been reported. However we do know that Japan, the largest holder of Treasury bonds, said expressly they would not be selling.

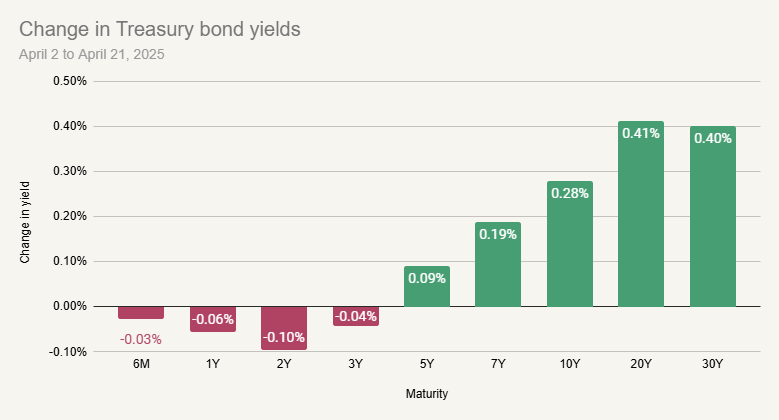

We can also take clues from how the Treasury market was trading. The chart below shows the change in Treasury bond yields at various maturities between April 2 (Liberation Day) and April 21, which was the peak for Treasury yields.

Source: Bloomberg

The chart shows that it was longer-term yields that rose substantially. Yields in the 2-5 year area only moved mildly. This is notable because foreign governments tend to own less very long-term bonds compared to those middle maturities. It's estimated that the average maturity of foreign government holdings is 6 years, suggesting the bulk of their holdings are between 2 and 10 years maturity.

The most common holders of 20 and 30-year maturities are insurance companies and pension funds. That these entities may have been selling bonds fits the story from above: private-sector global investors were generally allocating capital away from the U.S. This doesn’t look like foreign governments dumping dollars.

Could the dollar lose its status as the global reserve currency?

This is a question that has been asked for decades, and it's a fair one to ask now. However it's key to remember that there are many reasons why the dollar dominates not only foreign reserves, but also global trade. Most of those reasons haven’t been impacted by Trump’s tariff plans.

- Deep and liquid financial markets: The U.S. boasts the largest, most liquid, and most accessible financial markets in the world for stocks, bonds, and derivatives. This makes it easy for global investors and corporations to transact and invest trillions of dollars efficiently. This also makes the U.S. the most convenient place for global companies to hedge things like energy or agriculture prices.

- Trade invoicing: A vast majority of international trade, especially commodities like oil, is invoiced and settled in U.S. dollars, regardless of whether the U.S. is directly involved in the transaction.

- Ease of money movement: The U.S. has no capital controls (unlike countries like China) which means money can move between U.S. and non-U.S. banks relatively easily. It's also common for non-U.S. banks to allow dollar deposits, making the dollar all the more convenient to use.

- Large investor and consumer base: The sheer size of the U.S. economy and its consumer market makes the dollar central to global commerce.

- Lack of alternatives: While currencies like the euro or potentially the Chinese renminbi are sometimes discussed as challengers, neither currently offers the same combination of depth, liquidity, convertibility, and trusted institutional backing as the dollar on a global scale.

We wrote about many of these advantages in deeper detail in a prior article. Again, most of this hasn’t changed. Could recent events cause some shift in trade into euros or other currencies? Possibly. But the dollar’s position as the primary currency in global trade is unlikely to change anytime soon.

What if the dollar weakens further?

Could the dollar decline more from here? Absolutely. The outflows from global investors could continue, especially if the outlook for the U.S. economy weakens further. It's also possible that shifts in Federal Reserve policy relative to other central banks could impact the dollar. When interest rates drop more rapidly in one country vs. others, it's common for that currency to weaken.

However, for U.S. investors, a weaker dollar isn't necessarily a catastrophe, especially within their investment portfolio. If you hold a globally diversified portfolio including international stocks and bonds, a falling dollar actually boosts the U.S. dollar value of those foreign assets. When the dollar weakens, the returns earned in euros, yen, or other currencies translate back into more dollars. In this sense, standard global diversification already provides a natural hedge against dollar depreciation for your investments.

Do US investors need to hedge the dollar?

This brings us to the crucial point for individuals living in the U.S. If you are like most Americans, the vast majority of your expenses – housing, food, healthcare, utilities – are denominated in U.S. dollars. You don't face the direct risk of your home currency weakening significantly against the currency you need for daily life.

While a weaker dollar can make imported goods more expensive and increase the cost of foreign travel, your core living expenses remain dollar-based. Therefore, the need for U.S. individuals to actively hedge against a decline in the dollar itself is minimal. The primary impact you'll feel is through the value of your international investments (which benefits from a weaker dollar) and potentially higher prices for some goods. Trying to implement complex currency hedging strategies often adds cost and complexity with limited benefit for most U.S.-based investors focused on long-term goals.

Conclusion: Focus on fundamentals

While headlines about the dollar's decline can be attention-grabbing, it's important to maintain perspective. The dollar's recent weakness seems more related to investor positioning shifts than a fundamental loss of its dominant global role. For U.S. investors, the most practical approach remains focusing on a sound, globally diversified investment strategy. This diversification provides a sufficient buffer against currency fluctuations without the need for complex and often unnecessary direct currency hedging. This allows you to stay focused on your long-term financial goals.