The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- The economy added 142,000 jobs in August, which was weaker than expected.

- There were also downward revisions of 86,000 jobs for the prior two months.

- Job growth of this level is consistent with a growing economy, but the slowing rate of job gains is cause for some concern.

- The Federal Reserve is sure to cut interest rates when they meet in September. This report might convince them to cut even more aggressively.

Job growth rebounded a bit in the month of August according to data recently released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The U.S. economy added 142,000 jobs in August, up from 114,000 originally reported for July. However, that was a bit below expectations, and there was a significant downward revision to the last two months’ jobs numbers. Overall it paints a somewhat confusing picture. Here we’ll break down what this jobs number means to the overall economy, the Federal Reserve’s next move, and your portfolio.

Jobs kind of better, but kind of worse

Taken at face value, the employment picture improved from July to August. After revisions, the economy only added 89,000 jobs in July, and this rebounded to 142,000 in August. So that’s good. Plus the unemployment rate fell slightly from 4.3% to 4.2%. Also good.

On the other hand, markets were expecting a bigger rebound from July. According to a Bloomberg survey, economists were expecting 165,000 jobs added. On top of that, the prior two months were revised down by 86,000. This is a relatively large revision. You could combine these and say that the economy has 109,000 fewer employed people than economists were assuming before this report. That’s not great.

Is the economy headed for recession?

It is fair to ask whether the recent weakness in the labor market suggests a broader economic slowdown is coming. One reason why it is tough to analyze recession risk today is the fact this is a very unusual labor market. Typically when the economy nears a recession, companies start hiring less and laying off more workers.

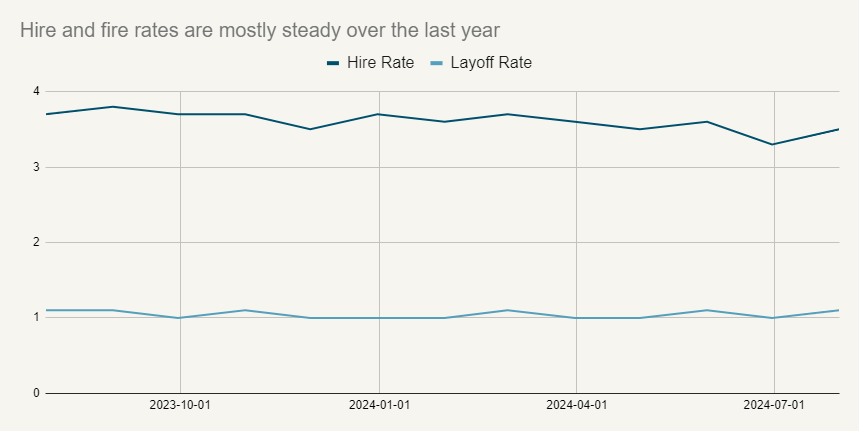

That’s not really happening right now. The chart below shows the rate of hires and layoffs over the last year. There has been a slight decline in the hire rate, but the layoff rate has been extremely consistent.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

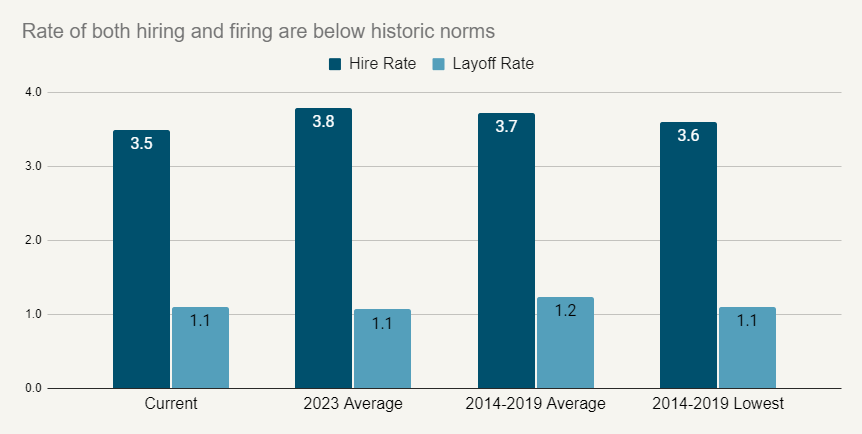

If we zoom out and compare today’s hire and layoff rates to past cycles, we see that both the hire and layoff rates are unusually low. That’s pretty odd. Logically one would assume that if companies are hiring new workers at an unusually low rate, that the pace of layoffs would be relatively high. But right now that is not the case. Both hire and layoff rates are lower than the lowest rate we saw from 2014-2019.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Economists are split on why this is happening. One theory I find compelling is the idea that companies are already running pretty lean due to a series of industry-specific recessions that have hit over the last four years. Over that period we have seen pretty big downturns in certain industries: home construction, freight, retail, parts of finance, parts of tech, among others. The downturns didn’t happen all at once, so there was no generalized recession. However as each of these mini-recessions hit, the impacted companies all got leaner with their headcount. If that’s true, then there might not be very many people left to cut.

Another theory that makes a lot of sense is that companies are worried that if they lay people off they won’t be able to staff back up when the economy improves. In 2018-2019 and again in 2021-2022, many companies reported that it was hard to find workers. Companies may prefer to keep more staff, even during a period of weakness, if that ensures that they’ll be at full strength during a rebound.

The combination of these two theories would explain why the labor market looks the way it does. It would also mitigate the risk of a broad recession. It is hard to get a recession without large scale layoffs.

What will the Fed do at their next meeting?

It is a given that the Fed will be cutting rates at their September 18th meeting. The question is whether they cut the traditional 0.25% or go with an outsized 0.5% rate cut.

This jobs report isn’t definitive either way. It isn’t weak enough to compel a 0.5% cut, but it isn’t strong enough to take it off the table either. Shortly after the number was released, futures markets indicated traders were split 50/50 on how much the Fed will actually cut.

Some of this will come down to what the Fed wants to communicate. A 0.5% cut would tell the market that the Fed is worried about economic weakness and wants to get ahead of it. In a recent speech, Fed Chair Jerome Powell strongly implied that the Fed intends on cutting at least multiple times in the coming months. So there wouldn’t be much hard in front loading those cuts now. They can always slow down the pace later if this bout of weaker labor numbers proves temporary.

Given that, I would lean that a 0.5% cut is somewhat more likely than a 0.25% cut. The balance of risks seems to be a bit skewed to economic weakness, and therefore it would make sense for the Fed to be a little aggressive with cuts here.

What does this mean for the stock market?

It has historically been the case that stocks generally rise as long as the economy keeps growing. Yes, there is volatility, but stocks rarely suffer a more extended and/or larger decline unless the economy falls into recession.

Given that, our view would be that whether stocks are higher over the next year hinges on this question: do we slip into recession? Or does the economy continue to grow?

In general, we don't engage in market timing regardless. However in this case specifically, we’ve already outlined some major reasons why this cycle could play out in an unusual way. If the economy does rebound, we would guess that stocks do relatively well in the coming year.

It is also the case that both consumer and corporate balance sheets are in strong shape. That could mean that if a recession begins near-term, it is a relatively mild one. In turn, that could mean that company profits hold up relatively well, which again could be good for stocks.

So our take is that it is better to build in some defensiveness within your portfolio, but not actually reduce overall exposure to stocks. For us, we’re accomplishing that by being overweight companies with higher profit margins, and underweight those with higher debt burdens, more profit variability, and generally exhibit more exposure to economic cycles. We think this is a better approach than trying to time markets or forecast recessions.