The information provided is based on the published date.

Key takeaways

- The US government's debt is high and continues to grow, but there is no immediate sign this will cause a financial crisis.

- The US dollar remains strong, and there is still demand for US Treasury bonds.

- The debt may have a minor impact on interest rates and inflation, but it's not the main driver of either right now.

- The bigger concern is the long-term sustainability of the debt, especially if interest rates continue to rise.

- However, this shouldn't be a major factor in your investment decisions today, because a crisis is likely many years away, if it happens at all.

The US government is approximately $27.5 trillion in net debt, an amount that has doubled since 2016. There’s no sign that the debt is going to shrink, with the Congressional Budget Office projecting $20 trillion in budget deficits over the next 10 years. So what does this mean for the economy and your investments? Is this something you should worry about? Here we’ll talk about how the growing US debt is and isn’t impacting your portfolio.

Keep your own politics out of investing decisions

As a citizen, you probably have preferences for how the government should spend its budget, how it should raise taxes, etc. However, it is crucial that as an investor you set those personal preferences aside. Similar to our advice about approaching elections, as an investor you want to focus on what will matter for company profits, economic growth, etc. Separate your feelings as a citizen from your analysis as an investor.

Government can always pay its debts

When it comes to thinking about debts, a government is not like a household. When you or I borrow money for something, we have to pay it back in a timely manner. That’s not how it works with the government. The US never has to pay back its debt in its entirety. It is perfectly sustainable for bonds issued today to eventually be paid back with new debts in the future.

In other words, when you personally borrow money, the appropriate question is “how am I going to pay this off?” For the US Treasury, the question is “how can we make sure we can keep issuing new bonds that the public wants to buy?”

Right now there’s plenty of demand for US bonds. One way we can see this is by looking at the auction results when the Treasury sells new bonds to the public. The chart below shows the ratio of bids for Treasury bonds vs. the amount the government planned to sell. We’ve included the most recent auction result for each major bond maturity over the course of March and April. In other words, for every $1 of bonds the government needed to sell, how much did they get in bids?

Source: U.S. Treasury

For example, on April 11, the Treasury sold $22 billion of bonds due in 30 years. That amount and the date of the auction is announced weeks in advance, with the Treasury taking bids from the public on the day of the auction. In this case, they got $52 billion in orders, for a ratio of 2.37 times the amount sold.

While this ratio bounces around from auction to auction, there’s been no signs that demand is being exhausted as the debt has grown. The bid ratio for the 30-year Treasury averaged 2.4 times over the 10-years ending 2019. Since 2019 total debt outstanding has risen by 60%, but the bid ratio has averaged exactly the same 2.4 times.

Dollar still as popular as ever

One of the major reasons why the world keeps buying up Treasuries is demand for the dollar. The US remains the largest and deepest financial market in the world, and this attracts capital from around the globe to buy all kinds of securities, including Treasury bonds.

We wrote an article last year about the potential for the dollar to lose its dominance, concluding that there was little evidence dollar demand was waning. Since then the dollar has only gained strength. From when that article was published on April 19, 2023, the dollar is 5% stronger vs. the Chinese renminbi and 3% stronger vs. the euro. According to the International Monetary Fund, foreign reserve holdings of dollars have increased by 3.5% over the last year, while renminbi holdings have declined by 9%.

Combining the data from Treasury auctions with continued strength of the dollar internationally, we can conclude that there’s no evidence that the world is about to give up on Treasury bonds. If the government’s debt load is going to cause a crisis, that moment is clearly some time away.

Given that, let’s talk about what impacts the size of the debt might be having on the economy right now.

Interest rates higher than they would be

It is almost certainly true that the rapid increase in Treasury debt over the last five years has had some effect on interest rates. One of the most basic concepts in economics is that as the supply of something increases, its price declines. In the case of bonds, a lower price means a higher interest rate.

However, it is hard to know how much the size of the debt is influencing interest rates. While rates have risen substantially over the last three years, that has coincided with a booming economy, a surge in inflation, and a record pace of Federal Reserve rate hikes. Those are all things that have traditionally resulted in higher interest rates.

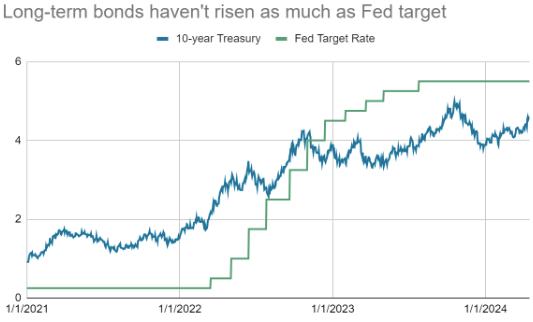

One way we could try to separate all these factors is by comparing the rise in longer-term rates to Fed rate hikes. If the world were becoming less willing to buy Treasury bonds, either because of worries about the US’s long-term health or simply too much supply of new bonds, we might expect bond yields to rise even faster than the Fed’s hikes. In reality the opposite has happened.

Source: Bloomberg

Since the start of 2021, the Fed has raised their target rate by 5.25%, but the 10-year Treasury yield has only risen by 3.69%.

That kind of pattern has been consistent in other countries. For example, Germany is an interesting one to consider since German debt levels have increased much less than in the US The Fed’s counterpart in Europe is the European Central Bank (ECB). Since 2021, the ECB has hiked interest rates by 4.50%, or 0.75% less than the U.S. Fed. Over that same time period, German 10-year bond yields have risen by 2.99%, or 0.69% less than U.S. 10-year bonds.

In other words, US bonds have moved in basically the same pattern as Germany once you correct for the fact that the ECB hasn’t hiked as much as the Fed.

All this is a roundabout way of saying, whatever the effect of large US bond supply has been on Treasury rates, the effect appears to be minor.

Is the deficit contributing to inflation?

Fundamentally, inflation is caused by total spending outstripping the economy’s ability to produce. Part of that spending equation could be government spending. In other words, if the government is buying goods and services, while not collecting any taxes to offset, that increases the total spending in the economy. If as a result, spending outpaces production, that would be likely to cause inflation.

However, the mere existence of a budget deficit isn’t inflationary in and of itself. Inflation is about a change in prices. So what matters is the change in government spending from one period to another. For example, over the last 12-months, total federal spending has declined by 6% over the prior year. That suggests the inflationary impulse from the deficit isn’t especially strong right now.

It probably also matters how the government spends. The inflationary impact of mailing out stimulus checks is probably different from sending aid to Ukraine as an example. In the former case, it creates fresh spending on current goods and services. In the later case, the money goes overseas and doesn’t impact the US economy much at all.

Source: Bureau of the Fiscal Service

To be sure, government spending was almost certainly a big reason why inflation started rising in 2021. Both President Biden and former President Trump passed large stimulus packages during COVID, but a lot of that money sat in savings accounts until COVID restrictions started easing up in 2021. The sudden burst in demand strained the economy’s ability to supply goods, which was at least a contributing factor to rising inflation during that period.

In addition, it is probably the case that a lower deficit would help reduce inflation. For example, if Congress were to raise taxes and/or cut spending, that would decrease overall spending in the economy. While that would probably decrease economic growth, it would help to reduce inflation.

All this is to say that the relationship between government deficits and inflation is complicated. All else being equal, a lower deficit would probably mean less inflation. On the other hand, since government spending isn’t rising right now, the deficit isn’t currently causing inflation to accelerate. We would also say that a lower deficit isn’t necessary to get inflation back down to normal.

How much debt is sustainable?

All in all, the increasing amount of US debt is probably only having a minor effect on the economy currently. The question is really whether this level of debt and deficit are sustainable over the long-run.

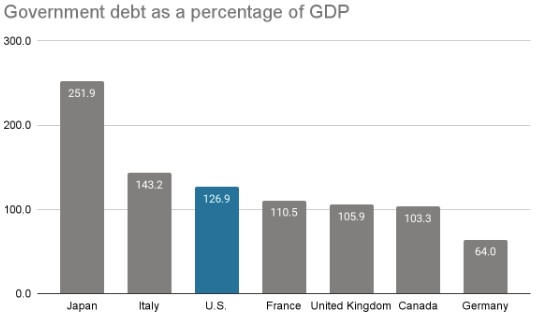

This is also not a simple question to answer. While the US debt burden is large, it is comparable to other large world economies measured as a percentage of gross domestic product or GDP.

Source: International Monetary Fund

One approach some analysts take is to assume that the debt can be sustained as long as it doesn’t grow as a percentage of GDP. Over the last year, US GDP grew 5.9% in current dollars. If debt growth were somewhat below GDP growth, say 4-5%, then debt would shrink as a percentage of GDP.

There are a few challenges. First, right now the debt is growing much faster than 4-5%. In the last 12-months, total debt grew about 11%. Growth at that pace is probably not sustainable.

The second challenge is rising interest rates. Interest owed on this large amount of debt builds up over time, and the fact that interest rates are relatively high now means that portion of spending is only going to grow. Right now interest payments account for about 13% of total spending, but that is projected to grow. The Congressional Budget Office projects that interest payments will increase by $700 billion over the next 10 years.

The third challenge is that GDP growth is relatively high right now. From 2009-2019, GDP growth averaged 4.0%. If economic growth reverts to that slower pace, it will be harder to keep the debt growing at or below GDP.

What does this mean for investing today?

Overall, the US debt’s impact on today’s economy and today’s investment markets are probably small. There aren’t any signs right now that the U.S. is struggling to find buyers for our debt.

That doesn’t mean there’s no reason for concern. There is definitely a risk that at some point in the future, the debt will become unsustainable.

In our view though, this isn’t something that should be influencing your investment decisions. First, it may take years or even decades before the Treasury actually has trouble selling debt. If at any time before that Congress makes even fairly minor adjustments to spending or revenue, the problem could be forestalled or eliminated completely.

Second, even if the moment comes where markets become less willing to buy Treasuries, Congress will have to make tough spending decisions. The cut in government spending could cause a recession, similar to what happened in Europe in 2011-2012. However, what if that moment is many years in the future? Stocks could double or triple while you wait for the disaster to come. Note that despite going through a financial crisis and a global pandemic, the S&P 500 is up more than 500% over the last 20 years. Even if stocks fall 25% during this far-off recession, you’d be better off having been invested during that whole period.

In general, it is very difficult to invest around very long-term macroeconomic issues. The economy has so many variables as it is, and in this case we’re also adding in a political variable. So much will invariably change over the coming decades. We think you are better off creating the best portfolio you can for today’s environment, and then continuously reassess. That is how we plan to approach investing for you going forward.

Tom Graff, Chief Investment Officer

Facet Wealth, Inc. (“Facet”) is an SEC registered investment adviser headquartered in Baltimore, Maryland. This is not an offer to sell securities or the solicitation of an offer to purchase securities. This is not investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. Past performance is not a guarantee of future performance.